“Syndemics” and “intersectionality”

“Syndemics” is a word that describes multiple and overlapping epidemics – such as HIV and hepatitis C. Although the OHTN loosely extended the term “syndemics” to include social and cultural factors in HIV Endgame: Stopping the Syndemics that Drive HIV, several presenters felt that the term “intersectionality” may have been more appropriate.

Coined by critical race theorist and civil rights activist Kimberlé Crenshaw in 1989, “intersectionality” describes the overlap between social categories such as race, class, and gender, especially in cases where these categories create systems of discrimination or disadvantage. In 2013, the OHTN produced a rapid response on intersectionality specifically related to HIV.

While the remainder of this report attempts to summarize conference presentations using the presenter’s terminology, several panelists, regardless of their chosen terms, spoke about the roles that racism, colonialism, homophobia, and transphobia play in stigma and health disparities. Intersectionality provides a useful lens for understanding, analyzing, and ultimately working to overcome these disparities.

Setting the stage to understand syndemics in Ontario

Sean Rourke, Scientific and Executive Director of the OHTN, introduced the overarching themes of the conference, highlighting the opportunity to combine knowledge from lived experience, research evidence, and practice.

“If we’re working in silos, and not looking at how we integrate and collaborate, it’s not going to work.”

Noting that people living with HIV are leading longer and healthier lives, he emphasized the OHTN’s vision of communities thriving now and beyond HIV, and the role that syndemics can play in complicating the five goals of Ontario’s provincial HIV/AIDS Strategy, which are:

- Improve the health and well-being of populations most affected by HIV.

- Promote sexual health and prevent new HIV, STI, and hepatitis C infections.

- Diagnose HIV infections early and engage people in timely care.

- Improve health, longevity, and quality of life for people living with HIV.

- Ensure the quality, consistency, and effectiveness of all provincially funded HIV programs and services.

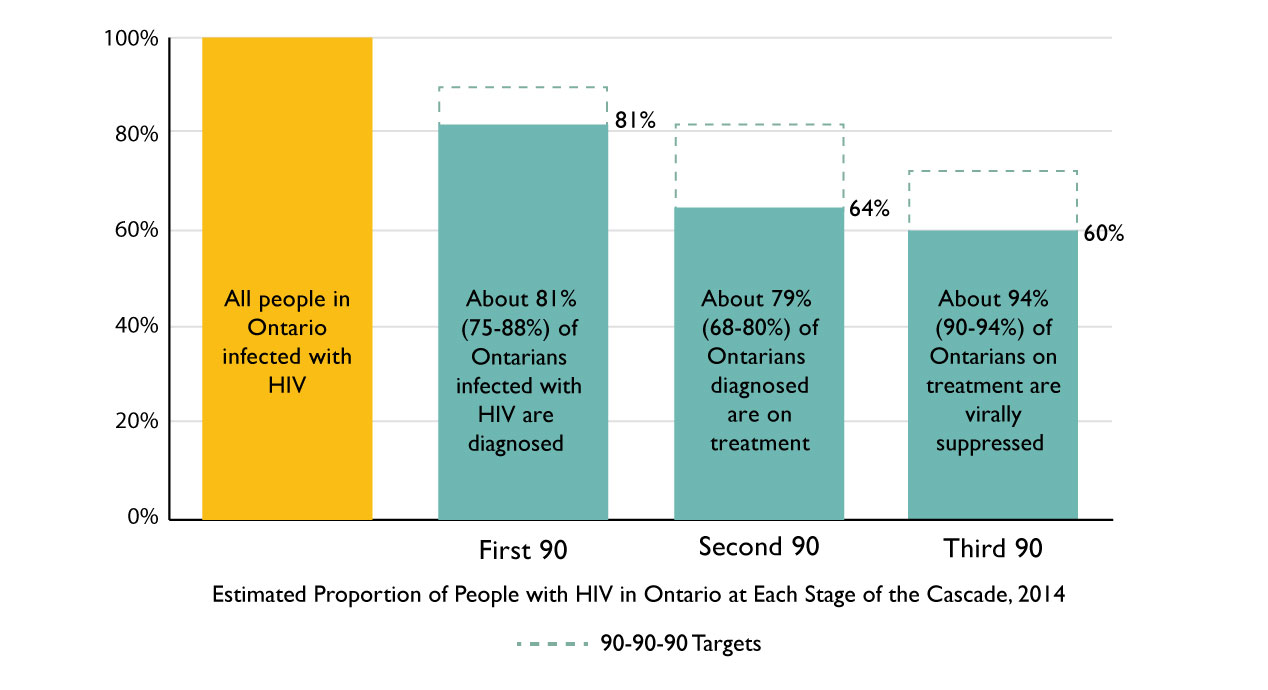

Turning to data from the Ontario HIV Epidemiology Surveillance Initiative (OHESI), Rourke explained that, although we’ve made progress in decreasing the number of new HIV diagnoses (842 in 2015), there is still work to be done. In terms of meeting the 90-90-90 targets set by UN AIDS, approximately 81% of Ontarians with HIV are diagnosed, and approximately 80% of those diagnosed are on treatment. Of those on treatment, approximately 94% are virally suppressed. That said, the compounding effect of gaps in diagnosis and treatment means that Ontario is still below all three UN AIDS targets.

Click here for an alternate text description of the graph above.

Data from the OHTN Cohort Study (OCS) shows that:

- 1/3 of participants have depression

- 1/3 have alcohol use issues

- 2/5 use tobacco

- 1/5 use recreational drugs

- 57% have experienced poverty

- 25% have a history of trauma and

- 38% have experienced intimate partner violence.

Several studies have shown that these and other syndemic factors are associated with worse physical and mental health outcomes, and that people who experience more than one are less likely to be in continuous care, on antiretroviral treatment, and have a suppressed or undetectable viral load.

Rourke concluded by asking attendees to consider what we can do to empower people living with HIV and build on their strengths and resilience.

Mapping the factors affecting ARV use among Indigenous people

Earl Nowgesic, of the University of Toronto, presented findings from the Indigenous Red Ribbon Storytelling Study, which was conducted with communities in Saskatchewan. The study examined how Indigenous people living with HIV construct and understand their experiences of antiretroviral (ARV) therapy use. Findings revealed that the majority of participants lived within three intersectional dimensions of social vulnerability:

- substance use

- living with HIV, and

- social context as a culture-sharing group impacted by relations with Canada.

Nowgesic presented a detailed causal loop diagram that depicted ARV therapy use among study participants. The diagram captures dynamic, non-linear systems of cause and effect – including biomedical, behavioral, and socio-cultural factors – that make people more or less likely to access, accept, and adhere to ARV therapy.

Explaining that complex systems such as this are adaptive and evolve in response to their environments, Nowgesic emphasized that, while it’s wrong to say that solving complex system problems will be simple, it’s also wrong to say that these systems are too chaotic to address. The causal loop diagram is one way of demonstrating the order underlying the way syndemic factors – including positive or negative thinking, embarrassment, discrimination, respect, health policies, and governing treatment – relate.

View the PDF of Nowgesic’s causal loop diagram. View an alternate text description of the diagram.