Questions

- What are best practices for communicating the harms of methamphetamine use to men who have sex with men in order to prevent its uptake?

Key take-home messages

- Focus groups within the community can provide useful insight on how methamphetamine is used among men who have sex with men in the local context (1, 2).

- Media campaigns aimed at discouraging use or uptake of methamphetamine among men who have sex with men have conflicting results (4).

- Using the sex-based sociality framework may have useful implications when designing education campaigns or harm reduction interventions among men who have sex with men (5).

- There is a dearth of research examining the spectrum of methamphetamine use between primary prevention and treatment; research examining contextual factors influencing methamphetamine is needed (1).

The issue and why it’s important

The use of methamphetamine among men who have sex with men, especially in the context of HIV risk, has been well-documented in the literature, and is associated with various drug- and sexual health-related harms (6). Men who have sex with men living with HIV who use methamphetamine are more likely to report high-risk sexual behaviours, incident sexually transmitted infections (STIs), and serodiscordant unprotected anal intercourse compared to their peers who do not use methamphetamine (7). Additionally, research has shown that initiation of methamphetamine use among HIV-uninfected men who have sex with men increases sexual risk behaviours (8).

Typically, methamphetamine use among men who have sex with men is discussed in the context of chemsex, which is defined as “…the use of drugs (specifically crystal methamphetamine, GHB [gamma-hydroxybutyrate]/GBL [gamma-butyrolactone] and mephedrone) before or during planned sexual activity to sustain, enhance, disinhibit or facilitate the experience” (9). Methamphetamine, in particular, is set apart by the specific “high” that users experience – it considerably increases the release of dopamine, impacting an individual’s judgment in ways other drugs do not (10). Frequent use of methamphetamine causes the brain’s natural stores of dopamine to deplete, leading to the development of anhedonia, the inability to feel pleasure (11). While there are no pharmacological treatments for methamphetamine use disorder, modest effectiveness has been shown in utilizing cognitive behavioural therapy, behavioural activation, and contingency management in the general population (12). Among men who have sex with men, some interventions, such as motivational interviewing and contingency management, have been reported to have significant effects on methamphetamine and/or sexual-health related outcomes (13).

This Rapid Response examines best practices for communicating sexual- and drug-related harms in order to prevent uptake of methamphetamine, and explores the groundwork for methamphetamine prevention efforts among men who have sex with men.

What we found

Methamphetamine prevention strategies

A 2015 Cochrane systematic review and meta-analysis by Allara et al. examined whether mass-media campaigns are effective in preventing the use of or intention to use illicit drugs among young people (<26 years) (14). By assessing these campaigns, authors sought to inform future strategies and campaign designs. Authors included 24 studies which corresponded to 19 unique interventions, all heterogeneous in terms of underlying theory, type of mass-media intervention, and outcome measures (14). Overall, Allara et al. found the evidence to be insufficient and inconsistent, and thus could not draw general conclusions. Only four interventions demonstrated evidence of beneficial effects: Above the Influence (alcohol and marijuana use) (15, 16), Be Under Your Own Influence (marijuana) (16), a televised anti-marijuana campaign broadcast (17), and The Meth Project campaign (14). By pooling findings of five studies from The Meth Project, Allara et al. found no evidence of a change in past-month use among young people aged 12-17 and 18-24, though there was evidence of a reduction in past-year use among those aged 12-17 (14). This campaign is discussed in further detail below.

Some research has demonstrated that the presence of disgust provides a persuasion-enhancing boost to appeals (i.e. messaging) based solely on fear (18). The Meth Project (formerly The Montana Meth Project) and Faces of Meth were two anti-methamphetamine media campaigns launched in the early 2000s that utilized images invoking fear, disgust, and shock in order to deter methamphetamine use; tactics used in these images were meant to capture the imaginations of potential users (19). Perceptions of both anti-methamphetamine campaigns were explored in a 2015 study that used photo-elicitation interviews with individuals who used methamphetamine (19). Participants (n=47) were presented with images from both campaigns to stimulate discussion (19). Respondents believed that the ads represented a certain type of methamphetamine user — one that did not reflect their own experiences (19). Thus, the images were generally ineffective at curtailing methamphetamine use (19). Additionally, all participants had seen images from both campaigns and stated that the ads had no impact on their decision to start or desist methamphetamine use in the past (19).

Other research supports these findings. Using data from the 1999–2009 Montana Youth Risk Behaviour Surveys (YRBS), Anderson (2010) examined the effectiveness of The Montana Meth Project on teen meth use, finding that the campaign did not contribute to a decrease in methamphetamine use among teenagers in Montana (20). A later study by Anderson et al. (2015) found results typically consistent with Anderson’s 2010 study, though there was some evidence of reduced methamphetamine use among white teens (21). In 2019, the governor of South Dakota launched an anti-methamphetamine campaign in order to raise awareness about addiction issues in the state (22). Developed by an independent creative advertising firm, the campaign features images of healthy South Dakotans on football fields and in coffee shops with the tagline “Meth. We’re on it.” (22). Los Angeles County also launched a methamphetamine awareness campaign in 2020 called Meth-Free LA County that utilizes the tagline, “You can come back from meth” (23).

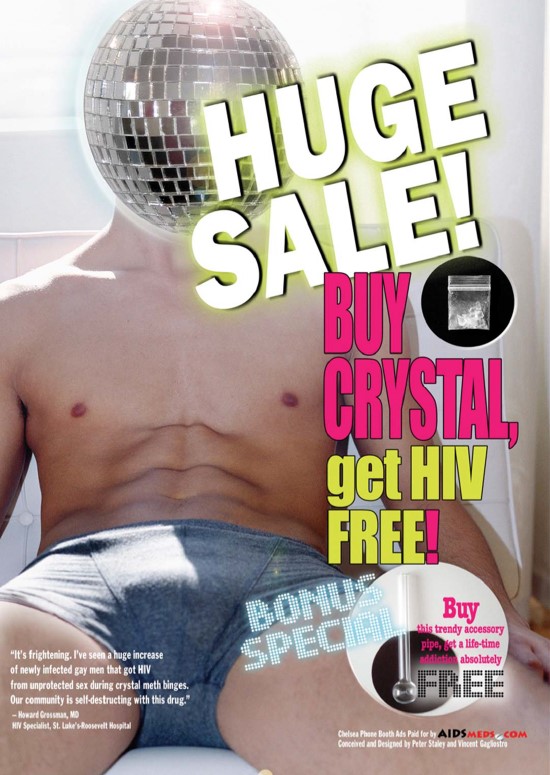

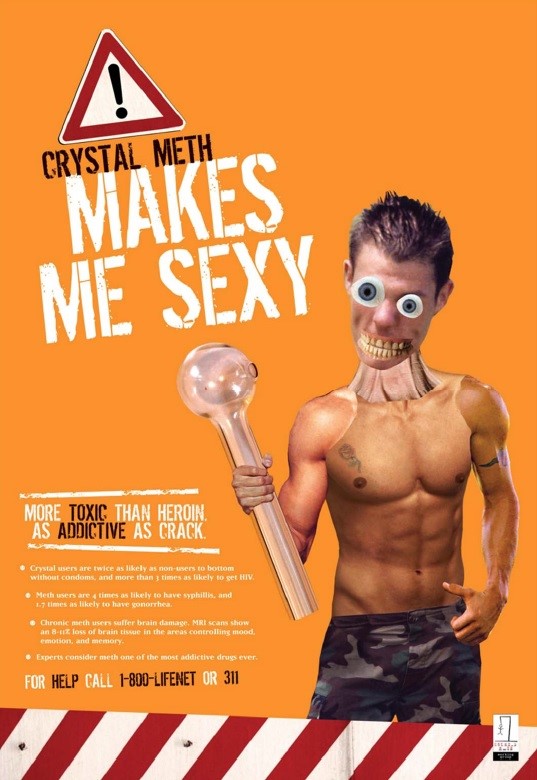

There have been other anti-methamphetamine visual campaigns that targeted men who have sex with men. Frustrated by the lack of public attention given to this growing issue, in January of 2004 AIDS activist Peter Staley spent his own money to produce a series of posters, and put them up in phone booth kiosks in a neighbourhood of in New York City (see Figure 1 for an example) (3).

Of note, the ads only featured white men, and were posted in an area of New York City that had a significant proportion of white gay and bisexual residents (4). The ads soon became a major news story, and two months later New York City appropriated government funds targeting methamphetamine prevention in gay men (24). Figure 2 is an example of another poster, produced in June 2005 by Staley’s own Crystal Meth Working Group (3). In an interview from 2004, Staley stated that the ads were his personal response to the lack of press and discussion around the issue, and that “…[t]hey were NOT meant to be educational. They were a political act…meant to provoke discussion and ultimately action by others” (25). An online biography of Staley from The Institute of Politics at Harvard University notes that “[A]ccording to ongoing CDC HIV surveillance studies, meth use among gay men in New York City fell from 14% in 2004 to 6% in 2008” (24). However, we were unable to identify the studies referred to in this article.

A study published in 2006 sought to determine the gay community’s reaction to this campaign by using a brief-intercept-survey method at two large-scale gay, lesbian, and bisexual community events in New York City (4). Gay and bisexual men over the age of 18 (n=971) who were potentially exposed to the campaign were included in the analysis (4). Respondents were asked if they had been exposed to the campaign; if they answered affirmatively, five more questions were asked about their responses to the ads. For example, “These ads made me think about not starting to use crystal or cutting down on my use” and “These ads made me want to talk to my friends/partner about their use of crystal” (4). Authors found that reactions to these campaigns were mixed: while white men, HIV-negative men, and men not using crystal methamphetamine responded more positively to the campaign, men who used crystal methamphetamine were more likely to report that the campaign triggered methamphetamine use (4). Of note, men of colour responded positively to the fourth question, which asked about discussing use with partners and friends. Additionally, men who did not identify as barebackers and who did not report unprotected intercourse with HIV serodiscordant partners agreed that they wanted to receive help to stop or avoid using crystal methamphetamine (4).

A study from Atlanta (2009) conducted focus group discussions and interviews with men who have sex with men who were using (but not addicted to) methamphetamine, community mental health providers, and AIDS risk-reduction specialists in order to inform a culturally-specific social marketing campaign and individual-based intervention (1). While funding for the campaign ran out and it was not launched, the qualitative data and preliminary campaign design may have elements useful for future research. To meet inclusion criteria, participants were casual users, who were not dependent on methamphetamine (1). Authors note that methamphetamine-related research among men who have sex with men often do not make this differentiation; the literature often misses the “middle range of the spectrum between primary prevention and treatment for methamphetamine dependence” (1). Other literature notes that research rarely explores different kinds of methamphetamine use and the variable relationship to harms (26, 27). For the focus groups and interviews, the three areas of inquiry were as follows: motivators for non-addictive (recreational) use, facilitators to avoid dependent use, and the need for local educations campaigns and intervention efforts (1).

There is an abundance of literature that describes why men use methamphetamine: to party, to cope (e.g. “escape”), for energy, and to improve self-esteem (28); to enhance sexual experiences and achieve greater intimacy (29); to increase libido, confidence, disinhibition, and stamina, but also to diminish guilt (30); and to be part of a gay community (31). While most of these sentiments were also echoed among men who have sex with men in the above-mentioned Atlanta study (1), exploring participant’s motivation to not become addicted added another dimension to understanding use. Facilitators to avoid heavier methamphetamine use included:

- contentment with current life functioning while fearing negative physical, occupational, and social consequences associated with more frequent use;

- observing negative behaviours of others (e.g. paranoia, “acting out”, isolation) who used frequently;

- witnessing the impact of methamphetamine dependence on physical health;

- failing to adhere to their anti-retroviral medication schedule (for participants living with HIV);

- viewing billboards and print advertisements discouraging methamphetamine use placed in the community (1).

In regards to the billboards and print advertisements, while they did raise awareness about the negative effects of methamphetamine, some participants found them to be non-educational (e.g. “Does it show me how to use more safely?”) and unrealistic (e.g. “I am a meth user and I haven’t died nor have my friends”) (1). However, the campaign was considered helpful because participants recognized it as the singular response to the methamphetamine problem in the community (1).

This qualitative data gathered in this study was intended to inform social marketing concepts; these would then be developed to target local, non-dependent users (1). These concepts would be evaluated within the community, eventually being integrated into HIV testing facilities in the area (1). Authors found that among all types of participants (including healthcare professionals), “…integrating a methamphetamine intervention with a MSM’s HIV test could be timely, efficient, and beneficial in producing sexual and other at-risk behavioral changes” (1).

Finally, a report based on data collected in 1998 outlines communication strategies for discussing methamphetamine use among men who have sex with men (2). Data came from interviews (n=13 participants) and focus group discussions (n=11 participants) from men in the U.S. (2). Suggested communication strategies included increasing the knowledge of negative effects of methamphetamine and designing culturally appropriate prevention efforts (2).

Sex-based sociality

Sex-based sociality is “…a unique, gay-community pattern of social relations and sexual interaction” (32). This framework focuses on how men who have sex with men socialize: in groups, where sexual expression and activity play a central role (32). A study from Australia explored the association between use of party-and-play drugs (meth/amphetamine, MDMA [methylenedioxymethamphetamine] or Ecstasy, cocaine, GHB, ketamine) and wellbeing among gay and bisexual men living with HIV (n=714) (5). From the sample, 29.7% (n=212) reported using party-and-play drugs at least once in the past 12 months; 5.3% (n=38) reported regular use. Compared to non-users, participants who occasionally or regularly used party-and-play drugs reported higher levels of resilience and physical functioning, and lower levels of perceived HIV-related stigma (5). Authors also found that crystal methamphetamine was more likely to be used in a social or sexual context rather than alone, noting the potential for the drug to facilitate intimate, sexual, and social connections (5). Additionally, these participants were more likely to spend time with and receive support from friends who identified as lesbian, gay, bisexual, or transgender and others who were living with HIV (5). Authors concluded that these results “…point to the likely importance of social support and connectedness in lessening the negative effect of stigma for people living with HIV” (5).

Generally, current literature lacks meaningful engagement with the social-sexual context in this population (32); some argue that because public health research tends to rely on biomedically-informed concepts of human behaviour or action, the studies typically reproduce individualised and often pathologizing understandings of drug use and call for research to engage with the historical, social, and political dimensions of methamphetamine use among men who have sex with men in order to understand how it is used as a social and sexual resource (26).

Factors that may impact local applicability

Engaging with methamphetamine-using men who have sex with men from the local community can help develop effective outreach efforts (8). While none of the included studies were conducted in Canada (and thus findings may not accurately represent the population of interest in Canada), it should be noted that using sex-based sociality as a framework may be useful in guiding research among this population, regardless of jurisdiction. Finally, identifying ‘best practices’ was difficult due to the dearth of research examining primary prevention of methamphetamine uptake among users.

What we did

We searched Medline (including Epub Ahead of Print, In-Process & Other Non-Indexed Citations) using terms (methamphetamine* or chemsex or crystal meth or meth) in titles AND (prevent* or campaign* or program* or intervention* or communicat* or strateg*) in titles or abstracts. Searches were conducted on October 14, 2020 and results limited to English articles published from 2010 to present. Google searches using various combinations of the search terms were also conducted. Reference lists of identified articles were also searched. Eight experts were contacted to provide additional information. The searches yielded 874 references from which 32 were included.

Reference list

- Dew BJ. Toward a better understanding of non-addicted, methamphetamine-using, men who have sex with men (MSM) in Atlanta. The Open AIDS Journal. 2010;4:141–7.

- Department of Health and Human Services: Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. Communication Strategy Guide. 2000. Available from https://www.urc-chs.com/sites/default/files/meth701.pdf Accessed October 29, 2020.

- Tuck A. Pleasure and desire in anti-methamphetamine posters targeting gay men. 2013. Available from: https://deepblue.lib.umich.edu/bitstream/handle/2027.42/107403/Tuck_Project.pdf?sequence=1 Accessed October 23, 2020.

- Nanin JE, Parsons JT, Bimbi DS, Grov C, Brown JT. Community reactions to campaigns addressing crystal methamphetamine use among gay and bisexual men in New York City. Journal of Drug Education. 2006;36(4):297–315.

- Power J, Mikołajczak G, Bourne A, Brown G, Leonard W, Lyons A, et al. Sex, drugs and social connectedness: Wellbeing among HIV-positive gay and bisexual men who use party-and-play drugs. Sexual Health. 2018;15(2):135–43.

- Rapid Response Service. May 2019. Sexualized drug use (chemsex and methamphetamine) and men who have sex with men. Toronto, ON: The Ontario HIV Treatment Network.

- Rajasingham R, Mimiaga MJ, White JM, Pinkston MM, Baden RP, Mitty JA. A systematic review of behavioral and treatment outcome studies among HIV-infected men who have sex with men who abuse crystal methamphetamine. AIDS Patient Care & STDs. 2012;26(1):36–52.

- Hoenigl M, Chaillon A, Moore DJ, Morris SR, Smith DM, Little SJ. Clear links between starting methamphetamine and increasing sexual risk behavior: A cohort study among men who have sex with men. Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes. 2016;71(5):551–7.

- Edmundson C, Heinsbroek E, Glass R, Hope V, Mohammed H, White M, et al. Sexualised drug use in the United Kingdom (UK): A review of the literature. International Journal of Drug Policy. 2018;55:131–48.

- Stuart D. Chemsex: Origins of the word, a history of the phenomenon and a respect to the culture. Drugs and Alcohol Today. 2019;19(1):3–10.

- Rusyniak DE. Neurologic manifestations of chronic methamphetamine abuse. Psychiatric Clinics. 2013;36(2):261–75.

- Paulus MP, Stewart JL. Neurobiology, clinical presentation, and treatment of methamphetamine use disorder: A review. JAMA Psychiatry. 2020;77(9):959–66.

- Knight R, Karamouzian M, Carson A, Edward J, Carrieri P, Shoveller J, et al. Interventions to address substance use and sexual risk among gay, bisexual and other men who have sex with men who use methamphetamine: A systematic review. Drug & Alcohol Dependence. 2019;194:410–29.

- Allara E, Ferri M, Bo A, Gasparrini A, Faggiano F. Are mass-media campaigns effective in preventing drug use? A Cochrane systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ Open. 2015;5(9).

- Carpenter CS, Pechmann C. Exposure to the above the influence antidrug advertisements and adolescent marijuana use in the United States, 2006–2008. American Journal of Public Health. 2011;101(5):948–54.

- Slater MD, Kelly KJ, Lawrence FR, Stanley LR, Comello MLG. Assessing media campaigns linking marijuana non-use with autonomy and aspirations:“Be Under Your Own Influence” and ONDCP’s “Above the Influence”. Prevention Science. 2011;12(1):12–22.

- Palmgreen P, Donohew L, Lorch EP, Hoyle RH, Stephenson MT. Television campaigns and adolescent marijuana use: Tests of sensation seeking targeting. American Journal of Public Health. 2001;91(2):292.

- Morales AC, Wu EC, Fitzsimons GJ. How disgust enhances the effectiveness of fear appeals. Journal of Marketing Research. 2012;49(3):383–93.

- Marsh W, Copes H, Linnemann T. Creating visual differences: Methamphetamine users perceptions of anti-meth campaigns. International Journal of Drug Policy. 2017;39:52–61.

- Anderson DM. Does information matter? The effect of the Meth Project on meth use among youths. Journal of Health Economics. 2010;29(5):732–42.

- Anderson DM, Elsea D. The Meth Project and teen meth use: New estimates from the national and state Youth Risk Behavior Surveys. Health Economics. 2015;24(12):1644–50.

- Zaveri M. ‘Meth. We’re on It’: South Dakota’s anti-meth campaign raises eyebrows. 2019. Available from: https://www.nytimes.com/2019/11/18/us/south-dakota-meth.html Accessed October 23, 2020.

- Reel360. Dept of Health launches meth awareness campaign. 2020. Available from: https://reel360.com/article/dept-of-health-launches-meth-awareness-campaign/ Accessed October 27, 2020.

- Harvard Kennedy School Institute of Politics. Peter Staley. 2016. Available from https://iop.harvard.edu/fellows/peter-staley Accessed October 23, 2020.

- Staley P. Crystal meth ads. 2008. Available from: https://www.poz.com/blog/crystal-meth-ads Accessed October 23, 2020.

- Bryant J, Hopwood M, Dowsett GW, Aggleton P, Holt M, Lea T, et al. The rush to risk when interrogating the relationship between methamphetamine use and sexual practice among gay and bisexual men. International Journal of Drug Policy. 2018;55:242–8.

- Moore D, Fraser S. Causation, knowledge and politics: Greater precision and rigour needed in methamphetamine research and policy-making to avoid problem inflation. Addiction Research & Theory. 2015;23(2):89–92.

- Nakamura N, Semple SJ, Strathdee SA, Patterson TL. HIV risk profiles among HIV-positive, methamphetamine-using men who have sex with both men and women. Archives of Sexual Behavior. 2011;40(4):793–801.

- Graf N, Dichtl A, Deimel D, Sander D, Stöver H. Chemsex among men who have sex with men in Germany: Motives, consequences and the response of the support system. Sexual Health. 2018;15(2):151–6.

- Weatherburn P, Hickson F, Reid D, Torres-Rueda S, Bourne A. Motivations and values associated with combining sex and illicit drugs (‘chemsex’) among gay men in South London: findings from a qualitative study. Sexually Transmitted Infections. 2017;93(3):203–6.

- Smith V, Tasker F. Gay men’s chemsex survival stories. Sexual Health. 2018;15(2):116–22.

- Hopwood M, Cama E, Treolar C. Methamphetamine use among men who have sex with men in Australia: A literature review. 2016. Available from: http://unsworks.unsw.edu.au/fapi/datastream/unsworks:43428/bin61273f84-da11-40ae-aadf-25e2dd9f7256?view=true&xy=01 Accessed October 21, 2020.

Suggested citation

Rapid Response Service. Communicating the harms of methamphetamine use to men who have sex with men. Toronto, ON: The Ontario HIV Treatment Network; December 2020.

Prepared by

Danielle Giliauskas and David Gogolishvili

Photo credit