Questions

- What are the best practices (including successes and challenges) of same-day HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) initiation after a negative HIV test result?

Key take-home messages

- Several clinics have implemented same-day PrEP programs and have reported that clinics offering this model of care, in general, have positive health outcomes (1–5). Studies also report that same-day PrEP is safe and feasible (2) and acceptable to patients (1).

- A review of same-day PrEP programs suggests that clinics with this model of care should have the ability to conduct specific point-of-care tests, draw blood for laboratory testing, contact patients, offer navigation services, and provide ongoing PrEP care (either onsite or through referral) (4).

- One study found that clinical assessment is an adequate method to identify patients eligible for same-day PrEP in settings that do not have access to laboratory testing, suggesting that same-day PrEP is a safe and promising model of care for clinics even with limited capacity (2).

- More research is needed to assess retention in PrEP care among patients who are offered a same-day PrEP (1, 6, 7).

The issue and why it’s important

Pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) refers to the coformulation of two antiretroviral drugs, emtricitabine (FTC) in combination with tenofovir disoproxil fumarate (TDF) or tenofovir alafenamide (TAF), which is taken to prevent permanent establishment of HIV when an individual is exposed to the virus (8). PrEP has shown to be effective in preventing acquisition of HIV upon exposure in men who have sex with men and transgender women (9), heterosexual men and women (10), and injection drug users (11). A strategy for individuals with an ongoing risk of infection, PrEP is highly effective in reducing the risk of acquiring HIV (12). Provision of PrEP through public health programming can play a major role in preventing transmission of HIV and has implications for curbing the HIV epidemic (13). Among others, this was demonstrated in a 2018 study from Australia, which found that HIV diagnoses in the state of New South Wales among men who have sex with men were drastically reduced following targeted, high-coverage implementation of PrEP (14).

In a review of strategies to streamline PrEP, Siegler et al. note that “[s]tandard care for HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP)…creates substantial burdens for patients, clinicians, and the healthcare system” (15). Authors suggest eleven strategies to streamline PrEP, one of which is same-day prescription of PrEP (15). This is in contrast to a referral model, where PrEP discussion and evaluation occurs at the initial appointment, with a subsequent referral to another clinic (15). Follow-up appointments are required once laboratory testing has been completed (15). Both of these scenarios have an inherent potential for loss to follow-up, as there can be delays of several days or more between initial patient contact and actual PrEP initiation (15).

Loss to follow-up in PrEP programming is demonstrated in a study from 2018 that examined the outcomes of an active PrEP referral program in Chicago, where PrEP eligible patients who presented at sexually transmitted infection (STI) clinics were actively referred to PrEP partner sites (16). Partner sites attempted to contact the patient within 72 hours, and the STI clinic followed up with PrEP partner sites to determine if the patient was actually linked to care (16). Of the 137 individuals who participated in the program, 31% (n=43) were linked, and 29% (n=40) received a PrEP prescription (16). Authors suggest that a model where PrEP is delivered on the day a patient presents could enhance uptake of PrEP; this would involve a same-day, on-site appointment in an STI clinic setting where PrEP starter packs may be provided, and where consent, contact, and linkage to care are consolidated (16). Clinic-based PrEP delivery models could ultimately contribute to a greater reduction in HIV incidence when compared to community-based delivery (1, 17).

This review examines same-day PrEP programs, describing the different settings where this model is used, and the associated successes and challenges.

What we found

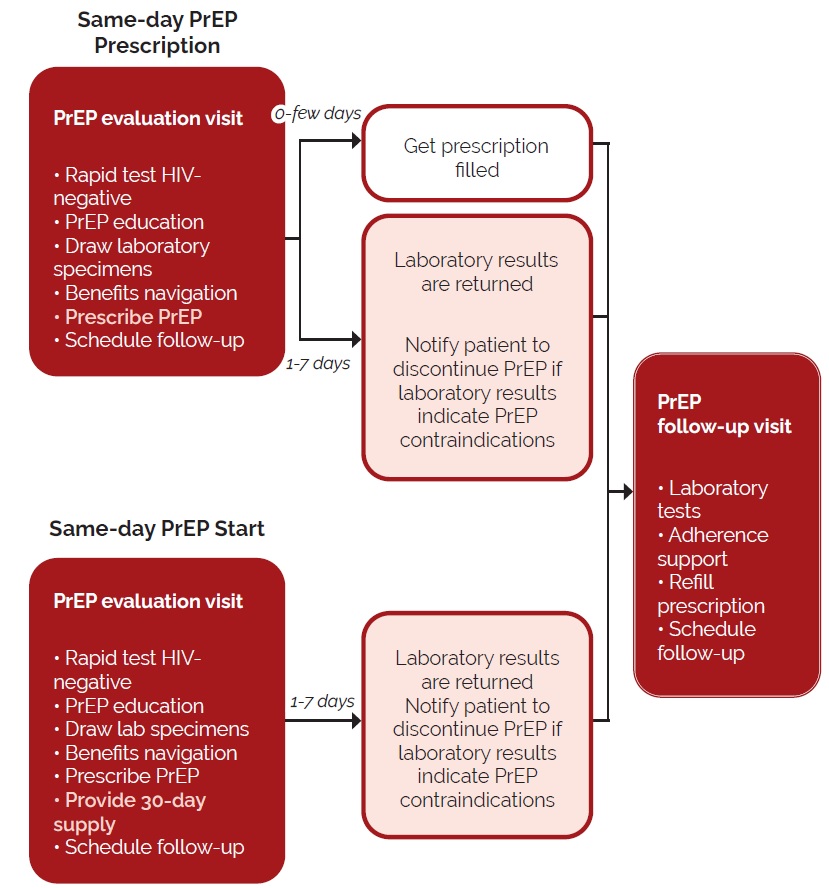

Same-day PrEP prescribing, and/or provision of medication via PrEP starter packs, is an emerging implementation approach intended to increase the uptake of PrEP (4). Same-day PrEP can generally be classified into two groups: same-day PrEP “prescription” programs, and same-day PrEP “start” programs (4). These two different models of same-day PrEP are illustrated in Figure 1 below, adapted from Rowan et al. (4). Note that the main difference between both of these models is that PrEP is provided either by prescription for same-day pickup or by a 30-day starter pack.

Figure 1. Same-day PrEP. Adapted from Rowan et al. 2021 (4)

In both models, a point-of-care HIV test is conducted to confirm that the patient is HIV-negative (4). This is important, as initiating PrEP may lead lead to HIV drug resistance if it is taken by an individual who is HIV-positive (18). However, it should be noted that the Canadian guidelines for PrEP initiation recommend that the most sensitive local assay available be used to determine HIV status — such as a fourth-generation assay or an HIV nucleic acid amplification test (NAAT) — as HIV is common in some populations where PrEP is indicated (12). While same-day PrEP does present a risk for individuals with undiagnosed acute or recent HIV infection (4), in clinical trials where PrEP was initiated in individuals with undiagnosed HIV infection, there were few cases of drug resistance (4, 19).

Rowan et al. note that “[k]ey elements of safe and effective same-day PrEP programmes include the ability to order laboratory tests at the time of the clinical visit and the ability to contact patients when laboratory results are available” (4). In the above diagram, both same-day PrEP models stipulate that in addition to an HIV point-of-care test, other laboratory specimens be drawn (4). Typically, laboratory evaluation of these specimens is completed and results are reviewed before PrEP is initiated (4). For example, at the Maple Leaf PrEP Clinic in Toronto, baseline laboratory tests are reviewed prior to treatment (20). Additionally, the PrEPStart program in Ontario provides free PrEP for three months to individuals who do not have drug coverage (21), though the prescription form requires physicians to confirm that the client’s kidneys are properly functioning (22). This is done by using a creatinine test to ensure that the client’s glomerular filtration rate is more than 60 mL/min (22). This is one of several baseline laboratory tests suggested by Canadian PrEP guidelines (12). Renal dysfunction is one of the issues to be considered in same-day PrEP programs (1), as TDF is a concern for nephrotoxicity (23). Generally, PrEP should not be prescribed in individuals with a history of renal disease until creatinine clearance is known (4). However, Rowan et al. do note that a point-of-care creatine test can be administered in the same-day PrEP start model (4).

Hepatitis B positivity is also another area for concern for same-day PrEP models (1). The U.S. Center for Disease Control and Prevention’s (CDC) clinical practice guideline for PrEP states that active hepatitis B virus infection is a potential safety issue for use of FTC in combination with TDF (TDF/FTC) (19). Additionally, Canada’s guidelines for PrEP note that if TDF/FTC is prescribed for someone with chronic hepatitis B infection, it may be necessary to consult with a qualified practitioner and perform appropriate monitoring (12). Results from the iPrEx study demonstrated that PrEP can be safely started or stopped in individuals with hepatitis B infection, as long as there is no evidence of cirrhosis or an elevation in transaminase (liver enzyme) levels (24), which can be a sign of liver damage (25).

There are several considerations that should be made before a facility can offer same-day PrEP (17). These include the ability to:

- Conduct point-of-care testing for HIV, creatinine, and pregnancy

- Draw blood for laboratory testing

- Contact patients should PrEP need to be discontinued

- Provide navigation services for insurance

- Provide follow-up appointments (onsite or through referral) for ongoing PrEP care (4).

The following examples describe same-day PrEP initiation programs where a rapid HIV test and a clinical assessment (e.g. a review of medical history) by a health care provider were conducted prior to starting PrEP and before results of baseline laboratory tests were received.

Models of same-day PrEP initiation

New York City Sexual Health Clinics

An abstract presented at the 2019 Conference on Retroviruses and Opportunistic Infections describes same-day, or immediate PrEP initiation (iPrEP) in New York City Sexual Health Clinics (SHCs) (2). While some same-day PrEP programs have the capacity to obtain specimens for laboratory testing prior to initiation of PrEP (5, 19), not all settings have these resources (5, 16); thus, the objective of this study was to determine the prevalence of medical contraindications for those who started PrEP at the SHCs (2). Following a non-reactive HIV test, the individual is clinically assessed (on the same day) for PrEP initiation (2). This assessment includes medical evaluation, HIV NAAT, hepatitis B serology testing, and metabolic panel testing (which includes a glomerular filtration rate kidney test) (2). If the medical assessment does not identify any contraindications, the individual is offered to start on PrEP before the results of laboratory testing are received (2). However, uptake of PrEP is delayed (dPrEP) if medical evaluation yields a history of kidney disease or hepatitis B infection, and if signs and/or symptoms of acute HIV are present (2). For ongoing PrEP care, both iPrEP and dPrEP patients are referred to external care (2).

Between January 2017 and June 2018, 1,437 individuals were evaluated for initiation of PrEP at the SHCs: 97% (n=1,387) qualified for iPrEP, and 3% (n=50) qualified for dPrEP (2). Of those who were in the dPrEP group, 12 had signs and/or symptoms of acute HIV infection, 16 had a history of kidney disease, nine had a history of hepatitis B, and 13 had other medical concerns surrounding PrEP (2).

The objective of the study was to determine the prevalence of medical contraindications to PrEP at the SHCs among both iPrEP and dPrEP patients, conducted via medical record review (2). Authors found that among all iPrEP patients (n=1,387), 99.3% (n=1,377) had no medical contraindications to PrEP; of those who did have a medical contraindication (0.7%, n=10), four had absolute contraindications (defined as a positive HIV NAAT and a glomerular filtration rate of <60 mL/minute) and six had relative contraindications (defined as a reactive hepatitis B surface antigen) (2). The four iPrEP patients (0.3%) who had absolute contraindications discontinued PrEP (2). Authors found that those who were ≥40 years of age were six times more likely to have contraindications compared to those who were younger (2). It was also found that among patients in the dPrEP cohort who had no medical contraindications to PrEP (n=43), only 35% (n=15) ended up initiating PrEP at SHCs within 60 days (2). Authors concluded that clinical assessment is an adequate method to identify patients eligible for same-day PrEP in settings that do not have access to laboratory testing, suggesting that this model of care at walk-in settings and sexual health clinics is both safe and promising (2).

Denver Metro Health Clinic

The Denver Metro Health Clinic is the largest STI clinic in the city of Denver, Colorado, and provides sexual health services at low or no cost, mainly through walk-in visits (1). A study was conducted to determine if a same-day approach to PrEP initiation was feasible and acceptable, and if it could be successfully implemented into this urban STI clinic (1).

While PrEP eligibility was assessed by a nurse, readiness to initiate PrEP and continue care at a participating clinic was established by consensus with the nurse, the overseeing physician, and the patient navigator (1). The patient navigator also provided PrEP education, conducted financial screening, followed up with patients after one week, and scheduled the one-month follow-up appointment at a participating clinic (1). Participating clinics included nine primary care clinics, two infectious disease clinics, and one private internal medicine clinic (1). The benefits of including patient navigation services in PrEP programming has been noted in a previous study in primary care clinics in San Francisco, which found that a patient navigation intervention was associated with earlier PrEP initiation (18).

Between April 2017 and October 2018, 584 individuals discussed PrEP with a provider; of these, 131 were referred to a patient navigator to be screened for enrollment in the study (1). Enrollees underwent screening for pregnancy, HIV, hepatitis B surface antigen, and serum creatinine (1). Results from the hepatitis B surface antigen and serum creatinine were available in one and two days on average, respectively (1). The final sample consisted of 100 individuals who started same-day PrEP (1).

Of the 100 participants, 98 were men who have sex with men and 19 reported having a partner living with HIV (1). Based on financial screening, 65 were linked to a PrEP financial assistance program (1). Of the 100 who started same-day PrEP, 18 were lost to follow-up, three discontinued due to side effects, and one moved out of state (1). Thus, 78 attended at least one PrEP follow-up appointment (1), and 57 attended at least two PrEP follow-up appointments (1). A follow-up survey was conducted three months after enrollment to assess satisfaction with the same-day PrEP program (1). Fifty-four percent (n=54) of all participants responded to the follow-up survey (1). All respondents liked having the option of same-day PrEP, 96% (n=52) reported that they would continue on PrEP, and 13% (n=7) reported difficulty initiating PrEP due to side effects and insurance challenges (1). Respondents also reported that taking PrEP was easy, convenient, and removed barriers (e.g. requirement of multiple clinic visits) (1). It was suggested that necessary paperwork required for financial assistance be reduced as it was time-consuming (1). Overall, authors concluded that same-day PrEP initiation, paired with patient navigation, was a safe and well-received model for PrEP care that had high acceptability (1).

After-hours sexual health clinic in Washington, D.C.

An abstract presented at the CDC’s 2019 National HIV Prevention Conference evaluated the feasibility of a pilot project for same-day PrEP initiation with linkage to care services at an after-hours sexual health clinic in Washington, D.C. (3). Those who presented to the clinic between May 2017 and February 2018 were offered additional counselling on PrEP (3). Individuals interested in starting PrEP received a short education session, medical visit, a rapid HIV test, and a fourth-generation HIV test (3). If the patient did not have a history of renal issues, active hepatitis B infection, or signs of acute HIV infection, a 30-day PrEP prescription was provided at the on-site pharmacy (3). Over the ten-month pilot period, 43 individuals were interested in PrEP; 97% identified as men who have sex with men, 3% identified as transgender female, and 35% reported a bacterial STI at baseline (3). Thirty-eight of the 43 individuals interested in PrEP received a prescription (3). Of these 38, 90% (n=33) initiated PrEP; the average number of days to pickup a prescription was 7.25, despite the colocation of a pharmacy and provision of navigation services (3). Twenty-four individuals (67%) linked to primary care for follow-up within one month, and of these, 71% (n=17) attended a follow-up visit at three months (3). Authors concluded that the pilot program demonstrated early success, but that more research is needed regarding factors related to PrEP initiation (3).

STI clinic in Mississippi

Express Personal Health (EPH) is a walk-in HIV/STI testing centre colocated in the same building as the Mississippi State Department of Health STD clinic (5). Same-day PrEP was offered to EPH patients who tested negative on a rapid HIV test and recommended for those who were diagnosed with a bacterial STI, had a partner with HIV or an STI, had a sexual relationship with a partner who was HIV-positive or of unknown status, used injection drugs, or was in an ongoing relationship with men who have sex with men (5). Staff at EPH discussed PrEP with eligible patients, and those interested in same-day PrEP were referred to an on-site pharmacist (5). The pharmacist then evaluated patients for acute HIV infection, considered their medical contraindications to PrEP, reviewed general medical history (including previous kidney disease or hepatitis B infection), and completed insurance paperwork (5). A 60-day prescription for PrEP was sent to the patient’s preferred pharmacy and a follow-up appointment was scheduled in six weeks for clinician’s evaluation (5). At this six-week appointment, baseline laboratory testing was conducted, including serum creatinine testing and hepatitis B testing (5). If the prescription was not picked up or if the client failed to attend their appointment, the pharmacist attempted to contact the patients weekly, for one month (5). All patient information was entered into a case management database by the pharmacist. In this pilot project, 69 patients were referred to the pharmacist for same-day PrEP between November 2018 and May 2019 (1). Of the 58% (n=40) who identified as men, 95% (n=38) identified as men who have sex with men (5). Nearly 20% of all participants were diagnosed with an STI or had a partner with an STI or HIV (5). Ninety percent of all patients (n=62) were seen by the pharmacist the same day as their rapid HIV test (5). All received a prescription for PrEP, and 77% (n=53) filled the prescription; of these, 43% (n=23) returned for a follow-up appointment within six weeks (5). Thus, 33% (23/69) filled the prescription for PrEP and were successfully linked to care (5). Authors concluded that integrating a same-day PrEP program into the nonclinical setting was feasible, but supports were needed to ensure retention in ongoing PrEP care (5).

The PrEP Program in St. Louis, Missouri

The PrEP Program has been offering same-day PrEP out of Washington University in St. Louis (WUSTL) Infectious Disease Clinic since August 2014 (4). This program was developed in response to user feedback from prior PrEP experiences, where users noted that multiple competing priorities made it difficult to attend multiple visits to the clinic and/or pharmacy (4). Similar to the aforementioned same-day PrEP programs, clinical screening, a point-of-care HIV test, and serum collection for laboratory testing are part of the initial visit; laboratory results are returned within 24 hours (4). If laboratory testing is not covered by an individual’s insurance plan, specialty partner pharmacies can administer a point-of-care creatinine test (4). Clients receive a 30-day prescription with a single repeat with follow-up appointments scheduled at one and three months, and navigation services for insurance are offered (4).

Rowan et al. report on some findings (based on unpublished data) from The PrEP Program (August 2014 to September 2018):

- Of the 334 individuals who received a PrEP prescription, 93% (n=311) were received on the day of intake

- Of those with same-day PrEP prescriptions, 97% (n=302) picked up their medication

- Of those who picked up their medication, 78% (n=236) continued on PrEP for at least three months

- Same-day PrEP prescribing resulted in faster receipt of a PrEP prescription and initiation of PrEP compared to usual care

- No prescription was discontinued due to abnormalities in laboratory test results

- No individual discontinued PrEP due to renal insufficiencies (4).

Howard Brown Health in Chicago

Howard Brown Health (HBH) is a large health organization in Chicago comprised of six clinics, with a patient base comprised primarily of sexual and gender minorities (7). While there does not appear to be published data specifically on the same-day PrEP program, Rowan et al. describe some of its features (4). In 2015, HBH established a protocol to offer same-day PrEP, which states that there is no reason to withhold a PrEP prescription on the day a patient presents for care (4). From 2012 to 2017, same-day PrEP prescription increased from 0% to 72% (4). Patients are given the option to take their first dose at the clinic via a 30-day PrEP starter pack, and collaboration with local community pharmacies ensures that these starter packs are routinely available (4). Baseline laboratory testing is completed, and within 30 days, all patients return for follow-up to assess for adherence, drug toxicity, and side effects (4). Rowan et al. report that since initiation of the same-day PrEP option, one client initiated TDF/FTC while living with HIV; the individual was switched to a TDF and emtricitabine-based HIV regimen with no evidence of viral resistance (4).

Mobile clinic services: Miami, Florida

The University of Miami offers a same-day mobile PrEP program (via a van) where same-day PrEP delivery occurs (26). The multilingual staff team consists of a medical provider, pharmacist, PrEP counselor, and logistics manager; patient recruitment is conducted through referrals and social media channels (27). Necessary laboratory evaluation is also arranged through the program (26). Of the 229 clients that were evaluated between October 2018 and April 2019, 73% (n=168) were eligible for PrEP (27). Of these, 78% (n=131) were Hispanic and 74% (n=125) identified as men who have sex with men (27). From the 168 who were eligible to receive PrEP, 99% (n=166) received PrEP; of those enrolled for more than three months, 71% (n=55) completed a follow-up visit (27). Authors considered the program to be both feasible and effective for engaging Hispanic men who have sex with men in Miami (27).

Other notable programs

Other programs in the U.S. also appear to be offering same-day PrEP, though limited information about these programs is available. A blog post from the Project of Primary health Care (PHC) in Iowa notes that Rapid Start PrEP was rolled out in May of 2020 as a way to overcome access barriers to PrEP; this program appears to streamline the process from receipt of a negative HIV test to PrEP prescription (28). Additionally, Philadelphia FIGHT Community Health Centers appears to also offer same-day PrEP, based on a published protocol (29). Eligibility and procedures for same-day PrEP appear to be similar to that of the programs discussed above (29).

Same-day PrEP initiation and retention in PrEP care

A retrospective cohort study from 2019 examined risk factors for disengagement in a comprehensive HIV prevention program in northern Manhattan, where PrEP is provided to men who have sex with men, transgender individuals, and heterosexual men and women who are at risk of contracting HIV (6). The program includes two HIV clinics and one sexual health clinic (6). Same-day PrEP is encouraged for eligible patients and made possible via partnership with local pharmacies (6). In this study, of the 696 individuals started PrEP; 210 (30.2%) were initially evaluated in the sexual health clinic (6). Of these, 104 (49.5%) had a same-day PrEP start (6). Among all individuals who started PrEP (n=696), retention in PrEP care at the third follow-up visit was 35.5% (n=247) (6). Authors found that <30 years of age, PrEP initiation in the sexual health clinic, and same-day PrEP start were all associated with lower retention in care (6). Authors note that it is unclear if same-day PrEP initiation contributed to higher rates of loss to follow-up and that more studies are needed to assess the impact of same-day initiation on retention in PrEP care (6).

Factors that may impact local applicability

All same-day PrEP models described in this review were located in the U.S. – none from Canada were identified. While all the programs generally had the same protocol, there were nuances in how PrEP was delivered, depending on the capacity of the clinic. Additionally, the included studies were completed with a variety of populations, and results may not be generalizable to particular groups. Furthermore, the relationship between risk perception, fluctuation of risk behaviours over time, and adherence to PrEP is complex (30) and should be considered.

What we did

We searched Medline (including Epub Ahead of Print, In-Process & Other Non-Indexed Citations, Ovid MEDLINE® Daily and Ovid MEDLINE®) using a combination of terms [initiati* adj3 or (PrEP or pre-exposure or preexposure)] in titles or abstracts AND term HIV in titles or abstracts. Searches were conducted on June 1, 2021 and results limited to English articles published from 2016 to present. Studies from low- and middle-income countries were excluded. Reference lists of identified articles were also searched. Google (grey literature) searches using different combinations of these terms were also conducted. The searches yielded 334 references from which 30 were included.

Reference list

- Kamis KF, Marx GE, Scott KA, Gardner EM, Wendel KA, Scott ML, et al. Same-day HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) initiation during drop-in sexually transmitted diseases clinic appointments is a highly acceptable, feasible, and safe model that engages individuals at risk for HIV into PrEP care. Open Forum Infectious Diseases. 2019;6(7):ofz310.

- Mikati T, Jamison K, Daskalakis D. Immediate PrEP initiation at New York City Sexual Health Clinics. 2019. Available from: https://www.croiconference.org/abstract/immediate-prep-initiation-new-york-city-sexual-health-clinics/ Accessed June 30, 2021.

- Coleman M, Godwin D, Logan M, Peer A, Cornell D. Abstract 5803 — PrEP initiation in a Washington D.C. sexual health clinic and linkage to primary care. 2019. Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/nhpc/pdf/NHPC-2019-Abstract-Book.pdf Accessed June 29, 2021.

- Rowan SE, Patel RR, Schneider JA, Smith DK. Same-day prescribing of daily oral pre-exposure prophylaxis for HIV prevention. The Lancet HIV. 2020;8:e114–20.

- Khosropour CM, Backus KV, Means AR, Beauchamps L, Johnson K, Golden MR, et al. A pharmacist-led, same-day, HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis initiation program to increase PrEP uptake and decrease time to PrEP initiation. AIDS Patient Care & STDs. 2020;34(1):1–6.

- Zucker J, Carnevale C, Richards P, Slowikowski J, Borsa A, Gottlieb F, et al. Predictors of disengagement in care for individuals receiving pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP). Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes. 2019;81(4):e104–e8.

- Rusie LK, Orengo C, Burrell D, Ramachandran A, Houlberg M, Keglovitz K, et al. Preexposure prophylaxis initiation and retention in care over 5 years, 2012–2017: Are quarterly visits too much? Clinical Infectious Diseases. 2018;67(2):283–7.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Pre-exposure prophylaxis: PrEP. 2020. Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/hiv/risk/prep/index.html Accessed June 25, 2021.

- Grant RM, Lama JR, Anderson PL, McMahan V, Liu AY, Vargas L, et al. Preexposure chemoprophylaxis for HIV prevention in men who have sex with men. New England Journal of Medicine. 2010;363(27):2587–99.

- Baeten JM, Donnell D, Ndase P, Mugo NR, Campbell JD, Wangisi J, et al. Antiretroviral prophylaxis for HIV prevention in heterosexual men and women. New England Journal of Medicine. 2012;367(5):399–410.

- Choopanya K, Martin M, Suntharasamai P, Sangkum U, Mock PA, Leethochawalit M, et al. Antiretroviral prophylaxis for HIV infection in injecting drug users in Bangkok, Thailand (the Bangkok Tenofovir Study): A randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled phase 3 trial. The Lancet. 2013;381(9883):2083–90.

- Tan DH, Hull MW, Yoong D, Tremblay C, O’byrne P, Thomas R, et al. Canadian guideline on HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis and nonoccupational postexposure prophylaxis. Canadian Medical Association Journal. 2017;189(47):E1448–E58.

- McCormack S, Dunn DT, Desai M, Dolling DI, Gafos M, Gilson R, et al. Pre-exposure prophylaxis to prevent the acquisition of HIV-1 infection (PROUD): Effectiveness results from the pilot phase of a pragmatic open-label randomised trial. The Lancet. 2016;387(10013):53–60.

- Grulich AE, Guy R, Amin J, Jin F, Selvey C, Holden J, et al. Population-level effectiveness of rapid, targeted, high-coverage roll-out of HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis in men who have sex with men: The EPIC-NSW prospective cohort study. The Lancet HIV. 2018;5(11):e629–e37.

- Siegler AJ, Steehler K, Sales JM, Krakower DS. A review of HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis streamlining strategies. Current HIV/AIDS Reports. 2020;17:1–11.

- Bhatia R, Modali L, Lowther M, Glick N, Bell M, Rowan S, et al. Outcomes of preexposure prophylaxis referrals from public STI clinics and implications for the preexposure prophylaxis continuum. Sexually Transmitted Diseases. 2018;45(1):50–5.

- Kasaie P, Berry SA, Shah MS, Rosenberg ES, Hoover KW, Gift TL, et al. Impact of providing preexposure prophylaxis for human immunodeficiency virus at clinics for sexually transmitted infections in Baltimore city: An agent-based model. Sexually Transmitted Diseases. 2018;45(12):791–7.

- Spinelli MA, Scott HM, Vittinghoff E, Liu AY, Morehead-Gee A, Gonzalez R, et al. A panel management and patient navigation intervention is associated with earlier PrEP initiation in a safety-net primary care health system. Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes. 2018;79(3):347–351.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Preexposure prophylaxis for the prevention of HIV infection in the United States — 2017 update: A clinical practice guildeline. 2018. Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/hiv/pdf/risk/prep/cdc-hiv-prep-guidelines-2017.pdf Accessed April 30, 2021.

- CATIE: Canada’s Source for HIV and Hepatitis C Information. The Maple Leaf PrEP Clinic: How does the program work? 2018. Available from: https://www.catie.ca/en/pc/program/maple-leaf-prep?tab=how Accessed July 6, 2021.

- The Ontario HIV Treatment Network. PrEPStart: What is PrEPStart? 2021. Available from: https://ontarioprep.ca/prepstart/ Accessed July 6, 2021.

- U.S. National Library of Medicine. Glomerular filtration rate. 2021. Available from: https://medlineplus.gov/ency/article/007305.htm Accessed July 6, 2021.

- Drak D, Barratt H, Templeton DJ, O’Connor CC, Gracey DM. Renal function and risk factors for renal disease for patients receiving HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis at an inner metropolitan health service. PLoS One. 2019;14(1):e0210106.

- Solomon MM, Schechter M, Liu AY, McManhan VM, Guanira JV, Hance RJ, et al. The safety of tenofovir–emtricitabine for HIV pre-exposure Prophylaxis (PrEP) in individuals with active hepatitis B. Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes. 2016;71(3):281–6.

- Giannini EG, Testa R, Savarino V. Liver enzyme alteration: A guide for clinicians. Canadian Medical Association Journal. 2005;172(3):367–79.

- University of Miami. The Mobile PrEP Program. 2021. Available from: https://med.miami.edu/departments/medicine/divisions/infectious-diseases/community-outreach/the-mobile-prep-program Accessed July 6, 2021.

- Mascolini M. High PrEP uptake, good follow-up, with mobile screening in Florida. 2019. Available from: https://www.natap.org/2019/IDWeek/IDWeek_22.htm Accessed July 7, 2021.

- The Project of PCH. Rapid Start PrEP. 2020. Available from: https://phctheproject.org/rapid-start-prep/ Accessed July 7, 2021.

- Sexual Information and Education Council of the United States. 38. Pre-exposure prophylaxis same-day initiation policies and procedures. 2015. Available from https://siecus.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/07/1.5-Sample-PrEP-Same-Day-Initiation.pdf Accessed July 6, 2021.

- Rutstein SE, Smith DK, Dalal S, Baggaley RC, Cohen MS. Initiation, discontinuation, and restarting HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis: Ongoing implementation strategies. The Lancet HIV. 2020;7:e721–e30.

Suggested citation

Rapid Response Service. Best practices of same-day HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) initiation. Toronto, ON: The Ontario HIV Treatment Network; July 2021.

Prepared by

Danielle Giliauskas and David Gogolishvili

Photo credit

Adapted from Jarun011 and ueligiezendanner