The Ontario HIV Treatment Network is strongly committed to diversity, resilience and health equity. To mark the International Day Against Homophobia, Transphobia, and Biphobia, and in solidarity with the communities we work to support, we asked our Knowledge Synthesis and Data & Applied Science Impact teams to share their findings on how discrimination impacts the health outcomes of people living with and at risk of HIV.

Homophobia, transphobia and biphobia are not abstract. The long-term health inequalities experienced by people who face discrimination are real, and increasingly well-documented. We wanted to use the data and science at our disposal to tell this story, particularly as it pertains to people living with and at risk of HIV.

What does the literature say about discrimination, health outcomes and HIV?

Health inequalities

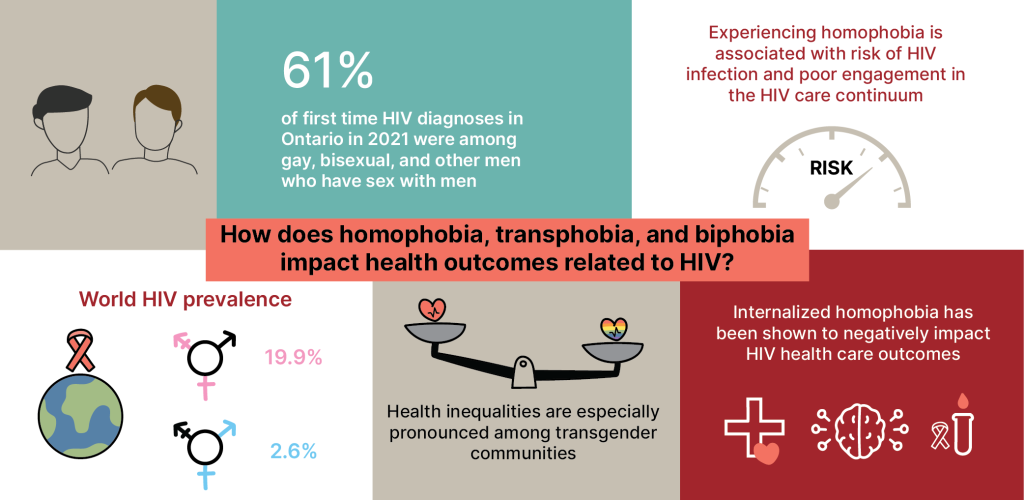

On May 17th 2004, the International Day Against Homophobia, Transphobia, and Biphobia was created to advocate for lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and intersex people and raise awareness of the ongoing rights violations, violence, and discrimination they experience.1, 2 As documented in a 2019 report by the House of Commons Standing Committee of Health of the Canadian Parliament, sexual minority communities across Canada experience many health inequities and are disproportionately affected by various health conditions compared to heterosexual individuals, including mental health disorders and HIV.3 For example, of 485 new first time HIV diagnoses in Ontario in 2021 reported by OHESI, 61% were among gay, bisexual, and other men who have sex with men.4 The knowledge synthesis team completed a review of recent academic literature to best understand current research findings on the impacts of homophobia and transphobia on mental and physical health.

Engagement in the HIV care continuum

In a meta-analysis of 44 studies from the U.S. published in 2021, experiencing homophobia was associated with risk of HIV infection, a diagnosed HIV infection, and poor engagement in the HIV care continuum among men who have sex with men living with HIV.5 These effects were more pronounced in studies with samples of mostly Black or Latino men who have sex with men, and for family-based mistreatment and perceived sexual minority stigma.5 Based on a large online survey of sexual health behaviours among 9,356 HIV-negative gay, bisexual, and other men who have sex with men from 45 countries, men were less likely to test for HIV and use pre- or post-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP or PEP) in countries with high levels of homophobia6 (drawn from the Homophobia Climate Index7). The country-level data also highlighted that homophobic attitudes coming from communities and health care staff can be a barrier to HIV care, and that the overall uptake of protective sexual health behaviours was significantly lower in countries with high levels of homophobia.6

Cyberbullying

In a 2022 study, 466 lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and questioning adolescents from a large U.S. city were surveyed on their experiences with homophobic cyberbullying.8 Overall, 48% of the participants revealed that they experienced this type of cyberbullying “almost all the time”, and 11% reported “all the time”.8 Homophobic cyberbullying was positively associated with symptoms of depression and anxiety.8

Internalized homophobia

Internalized homophobia (inward direction of societal homophobic attitudes at an individual level, including the internalization of negative attitudes conflicting with self-regard)9 has also shown to impact HIV health care outcomes. For example, of 907 cisgender gay and bisexual men with an HIV-negative or unknown HIV status, those with high levels of internalized homophobia had a lower prevalence of testing for HIV compared to participants with low levels of internalized homophobia.10 In another study observing 322 sexual minority HIV-negative men of colour aged between 18 and 34, HIV-related knowledge decreased as internalized homophobia increased, .which may result in individuals delaying seeking HIV-related health care.11 Internalized homophobia has been significantly associated with an increased prevalence of internalizing mental health disorders, including depression, anxiety, and stress-related disorders.9 In a survey of 404 sexual minority adults, self-esteem, emotional stability, and general self-efficacy mediated the relationship between internalized homophobia and suicide ideation via depressive symptoms.12 Internalized homophobia has also been linked with drug-related problems: in a 2018 study analyzing responses of 1,071 gay and bisexual men, internalized homophobia was positively associated with depression, and depression was positively associated with recent drug use.13

Transgender communities especially impacted

Health inequalities are especially pronounced among transgender communities. For example, in a 2022 systematic review, HIV prevalence among transgender women in high-income countries in North America, Europe, and Australia (i.e. the Global North) was found to be 17.1%.14 This number is higher among transgender communities in many other parts of the world, resulting in a global HIV prevalence of 19.9% for trans feminine individuals and 2.6% for trans masculine individuals.14 In the U.S., it is estimated that among transgender women and transgender men, HIV infection prevalence is 14.1% and 3.2%, respectively.15 Black and Hispanic transgender women are particularly vulnerable, with a significantly higher prevalence estimate (44.2%) compared with White transgender women (6.7%).15 Transgender people face unique challenges in their lives rooted in transphobia, stigma, and discrimination, resulting in poor health outcomes. Only 186 participants (13.9%) indicated that they had predominantly experienced gender-sensitive sexual health care. For example, a majority of 1,613 transgender and gender diverse people in Australia who responded to an online sexual health and well-being survey, reported cisgenderism (a form of stigma that denies, ignores, and marginalizes genders other than those that adhere to a fixed gender binary16, 17) and transphobia (negative feelings, attitudes, or actions directed towards transgender people) while accessing sexual health care.17 Only 186 participants (13.9%) indicated that they had predominantly experienced gender-sensitive sexual health care.17 These experiences were associated with a lower likelihood and frequency of HIV/STI testing.17 In another example, HIV risk among 149 transgender women in San Francisco was measured based on the occurrence of any condomless receptive anal intercourse with the last six partners and binge drinking (i.e. any occasion of consuming five or more drinks in one episode), both within the previous six months.18 Transgender women who reported high levels of transphobic discrimination were 3.5-times more likely to have engaged in recent binge drinking compared to those reporting a low level of transphobic discrimination, and transgender women of colour were almost 3 times more likely to have experienced condomless receptive anal intercourse compared to White transgender women.18

Transphobia and mental health

Literature has also identified how transphobic experiences negatively impact mental health outcomes of transgender communities. Among 233 surveyed transgender women in the U.S., transphobia-based violence was significantly related to anxiety, depression, and body satisfaction; body satisfaction was also associated with the diagnosis of mental health disorders.19 Additionally, relationships were identified between internalized transphobia and anti-transgender discrimination, depression, and anxiety in a study analyzing 149 transgender and gender nonconforming Italian individuals.20 Among 207 surveyed Korean transgender men and women, there was a high prevalence of depressive symptoms, suicidal thoughts, and suicide attempts across the participant responses.21

More research needed

Research and literature on health outcomes for bisexual men and transgender men is limited: a 2022 systematic review assessing HIV care outcomes among transgender people with HIV emphasized the lack of studies on transgender men.22 Similarly, in most research, bisexual men are grouped with men who have sex with men and their data usually are not analyzed separately.13, 23

Overall, calls have been made for policymakers and other stakeholders to enhance health systems and services to combat negative health outcomes associated with homophobia, transphobia, and biphobia.9, 11, 19, 21, 24

Childhood Bullying among 2SLGBTQ+ participants in the OCS

The research literature clearly shows that homophobia, transphobia and bi-phobia have important impacts on health. To know how to respond in Ontario, we turn to our own research to understand the local context. The OHTN cohort study (OCS) conducts an annual interview with participants living with HIV, which includes many health related questions and a recent focus on trauma, bullying and discrimination.

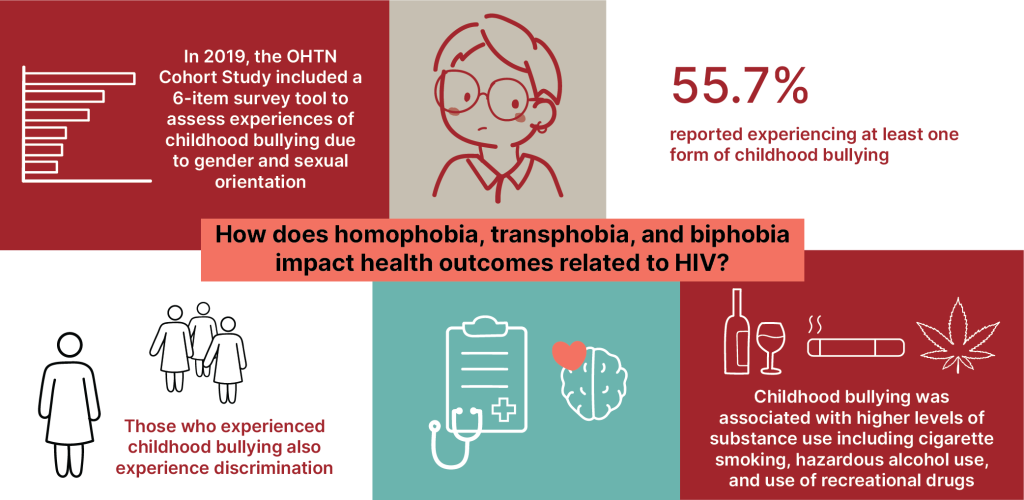

In 2019, the OCS included a 6-item survey tool to assess experiences of childhood bullying due to their gender and sexual orientation. 2SLGBTQ+ participants were asked if, during their first 18 years of their life, they were verbally bullied or harassed at home/school, physically bullied or harassed at home/school, sent to a professional (e.g., therapist, counselor, religious advisor), kicked out of the house, family members (s) stopped talking to them for a long time or ended the relationship, or a family member was violent towards them.

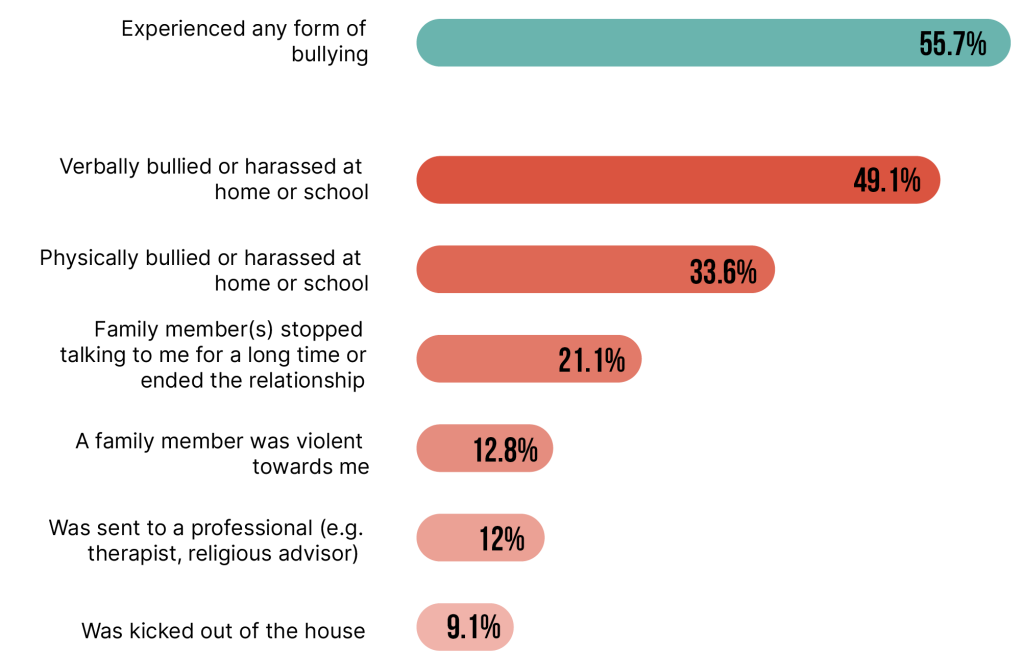

Of the 1,645 2SLGBTQ+participants who provided information (2019 to 2022), 917 (55.7%) reported experiencing at least one form of childhood bullying (Figure 1). The three most common forms of bullying reported were verbal bullying or harassment (49.1%), physical bullying or harassment (33.6%), and a family member stopped talking to me for a long time or ended the relationship (21.1%).

Figure 1. Experiences of childhood bullying among 2SLGBTQ+ participants (N=1645)

Prevalence of childhood bullying was highest (73.2%) among participants aged 30 to 39 years and declined significantly with increasing age, with the lowest prevalence among people 70 years or older (30.5%). Prevalence of childhood bullying varied significantly (p<0.001) by sexual orientation: 65.3% among Queer/’Other’, 60.0% among Lesbian, 58.0% among Gay, and 31.1% among bisexual participants. It also varied by gender (p<0.001), with 83.9% among people who identified as Two-Sprit, Transgender, or Gender Queer,56.1% among men, and 32.3% among women. Highest prevalence of childhood bullying was reported among participants who identified as Latinx (69.9%) and the lowest prevalence was among people who identified as Arab/West Asian (38.1%).

Childhood bullying and poor health outcomes

2SLGBTQ+who experienced childhood bullying reported significantly higher levels of hazardous alcohol use in the past year (33.8% vs. 28.6%, p<0.05), cigarette smoking in the past 30 days (28.2% vs. 21.0%, p<0.001), and recreational drug use in the past 6 months (24.3% vs. 16.4%, p<0.01) and were more likely to report at least one diagnosed mental health condition (39.2% vs. 24.1%, p<0.001) and higher level of depressive symptoms (21.4% vs. 11.5%, p<0.001), compared to 2SLGBTQ+ who did not experience childhood bullying.

Experiences of discrimination

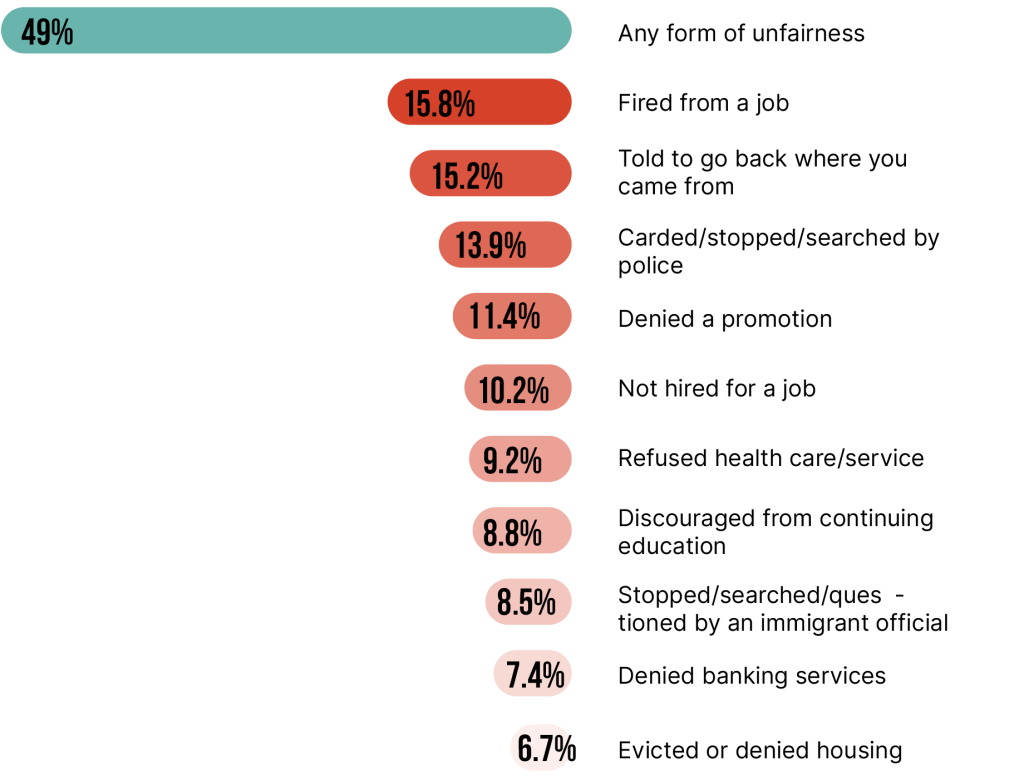

Among the 1645 2SLBGTQ+ who provided data on childhood bullying, 1550 (94.2%) of them also were asked if they ever experienced unfairness and discrimination (Figure 2). 760 (49.0%) of them indicated that they were treated unfairly and the three most common types of unfairness reported were being fired from a job (15.8%), told to “go back” to where you came from (15.2%), and carded, stopped, searched, or questioned by police (13.9%). 126 (16.6%) of the 760 2SLBGTQ+ who experienced unfairness indicated that they were discriminated because of their gender or sexual orientation.

Conclusions

Homophobia, transphobia and biphobia are shown to have significant impact on mental and physical health. While more research is necessary to fully understand the across the 2SLGBTQ+ spectrum, the results are clear. Interventions and policies that respond to and limit discriminatory behaviours will improve overall health, as well as support the prevention of HIV and improve the well being of people living with HIV.

Figure 2. Experiences of unfairness and discrimination among 2SLGBTQ+ participants (N=1550)

Table of references available in PDF version of report.