Question

- What evidence exists for the use of comic books, graphic novels, and fotonovelas as health promotion tools (including HIV and STIs)?

Key take-home messages

- Comics — including graphic novels, comic books, and fotonovelas — are one way to learn and teach about illness (1) as the reader can relate words and images to personal experience (2, 3).

- Generally, comics focused on health can fall into two different categories: memoirs about personal health or an experience of illness, and comics that consist of instructional content designed for education (4).

- The Undetectables Intervention utilized a comic book series alongside interdisciplinary adherence support teams and financial incentives to promote adherence to HIV medication with favourable results (5).

- Fotonovela interventions demonstrated positive outcomes for several health conditions (6-8).

- There appears to be a limited amount of literature describing how to design or evaluate comics for health promotion purposes.

The issue and why it’s important

Visual narratives consist of literature that conveys a story through images and words (9, 10). One kind of visual narrative is the comic, which contains “juxtaposed pictorial and other images in deliberate sequence, intended to convey information and/or produce an aesthetic response in the viewer” and may or may not include words (11). Graphic novels, such as Maus by Art Spiegelman (12), and comic strips, like Calvin and Hobbes by Bill Watterson (13), are both examples of comics. Similar to these traditional types of comics is the fotonovela (also known as a photonovel or photo-comic), a medium comprised primarily of still photographs and text rather than illustrations, and widely read in Latin America (14).

Typically, a comic features two systems of coding — text and images — which can function independently or interact (3). As a result, the reader must actively ”participate” in the comic to establish basic meaning (15); this is created by relating words and images to personal experiences (2, 3). Thus, comics have a unique ability when compared to traditional texts: they are able to engage the reader by activating rational and emotional styles of learning (16). A comic allows the reader to “…construct, critically interpret, and consciously reflect on and relate to specific messages” (15).

In recent years, academic publications have explored the intersection of visual narratives and medicine (1, 3, 17), noting the utility and benefit of visual messaging elements to communicate health information (18). This has developed into a subfield known as graphic medicine: how sequential, visual storytelling is used to share health-related experiences and information (18). Comics — presented in a variety of mediums — are the visual narrative most relevant to the study of graphic medicine (18).

This review explores how graphic medicine is used in medical education and patient care, examining evidence that supports the use of graphic medicine as a health education tool. While the specific focus is on HIV and other sexually transmitted infections (STIs), comics detailing other illnesses are also considered.

What we found

HIV, AIDS, & STIs in comics: A brief history

Ian Williams, a comics artist and physician, was the first to coin the term graphic medicine, developing the website www.graphicmedicine.org in 2007, and completing a Master’s dissertation on the topic in 2009 (19). In 2010, an article in the British Medical Journal acknowledged Williams as the originator of the term (1).

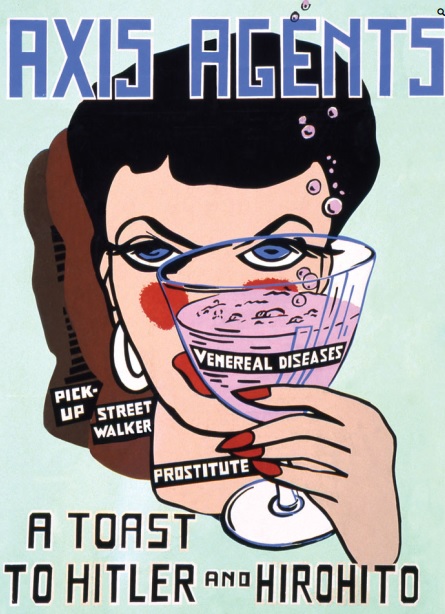

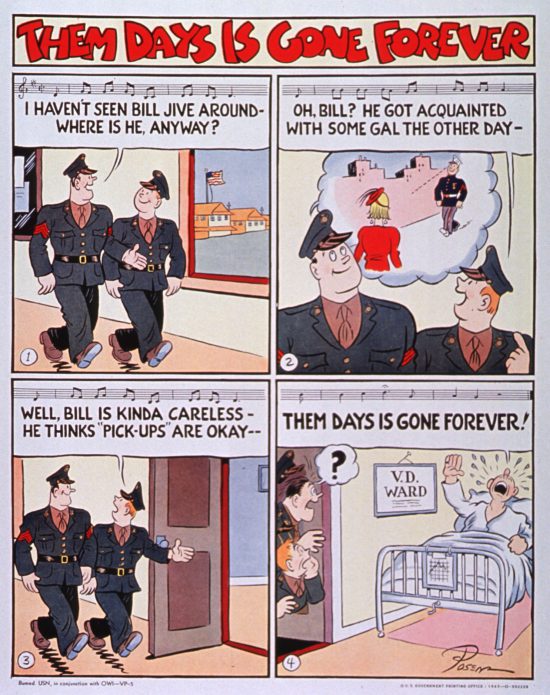

However, health care and visual narratives were interacting decades before the term graphic medicine debuted. During World War I and II, the American Social Hygiene Association and the U.S. War Department developed an aggressive anti-venereal disease campaign (20, 21) with the intent of educating soldiers, though “educating” was often was secondary in the messaging (22, 23). Generally, the posters encouraged soldiers to abstain from sexual contact as it was deemed unpatriotic, dangerous, and shameful to a spouse or girlfriend back home; additionally, women were portrayed in a negative light (22, 23). The impact graphic propaganda had on reducing the incidence of venereal diseases appears to be unclear. One source cites a 50% drop in incidence rates in the military at the beginning of World War II (21), while another claims that venereal disease rates did not reflect the nation’s efforts (24). The following graphics are examples of these posters (23, 25).

The onset of HIV in the 1980s continued to foster the interaction of comics and STIs. In 1992, an article from the Journal of Popular Culture analyzed the relationship between AIDS and comic books, identifying three ways that comics were integrating education and AIDS (27). Firstly, by offering education specifically about AIDS; second, by including fictional characters living with AIDS into storylines and characters; and finally, by donating profits made from the sale of AIDS-related comics to AIDS causes (27).

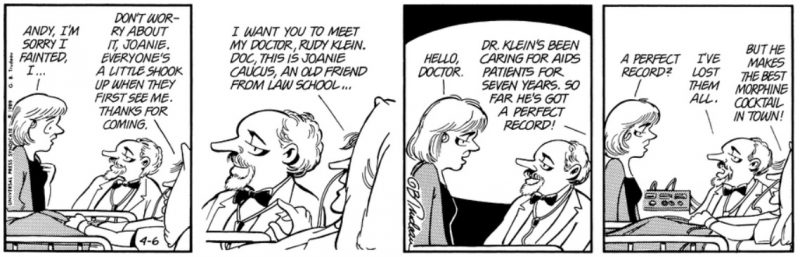

One example of a well-known comic strip that highlights two of the points above is Doonesbury by Garry Trudeau. In 1976, Andy Lippincott, a fictional character from Doonesbury, was the first openly gay character in a comic strip (28). In April of 1989, Doonesbury followed the reunion of Andy and a friend during his hospital treatment for AIDS; he eventually dies in a strip published in 1990 (28). Not only did Trudeau’s comic strip challenge the stereotypes and fears the public had of AIDS, but it brought a lighthearted aspect of the illness to health care workers and their patients who often dealt with loss (28). Furthermore, Andy handled his illness with dignity, kindness, and humour; this helped other characters, as well as readers, gain a better understanding of the illness (28). Some of these elements are illustrated in the Doonesbury comic strip below, from April 6, 1989 (29) (reprinted with permission from Andrews McMeel Syndication):

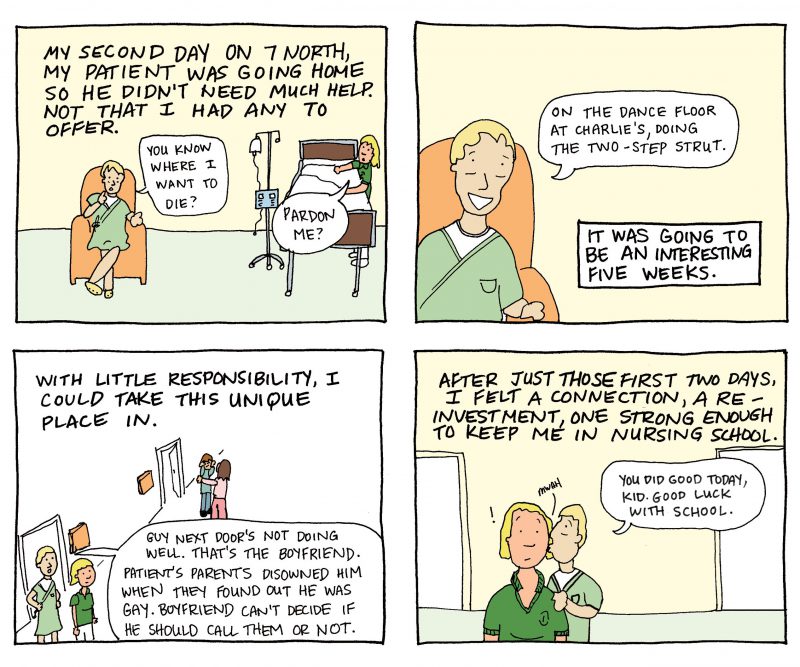

More recently, graphic novels chronicling real people’s experiences of illness have been published (1). One example of this is Taking Turns: Stories from the HIV/AIDS Care Unit 371 by Mary Kay Czerwiec (30). As a young nurse in the 1990s, Czerwiec took her first nursing job at Illinois Masonic Medical Center in unit 371, which provided exclusive care to people living with HIV and AIDS (31). The graphic novel chronicles her experiences: Czerwiec reflects on her own naïveté, the rise of gay identity in Chicago, the hospital’s art program, and how medical professionals contended with bigotry from patient’s families (32). Additionally, Czerwiec recounts stories of individual patients (32). The comic strip below outlines an interaction between Czerwiec and a patient (30) (reprinted with permission from Penn State University Press):

Types of health-focused comics

Generally, comics that are focused on health can fall into two different categories: memoirs about personal health, medical, or an illness experience, and comics that consist of instructional content designed for education (4). Taking Turns: Stories from the HIV/AIDS Care Unit 371 is one example of a comic that would fall into the first category.

Comics like Taking Turns are thematically similar to standard accounts of illness that rely only on text to communicate a message; however, graphic narratives of illness are able to produce “…powerful visual messages [that] convey immediate visceral understanding in ways that conventional text cannot” (1). The images, stories, and perspectives presented in these narratives can act as a window into the lives of patients, evoking an understanding unlikely to be gained from reading pure text or visiting a clinic (33). Furthermore, embedding dialogue and narrative into graphics (as in the above example from Taking Turns) allows the reader to connect with multiple layers of a character’s experience (33). As a result, empathetic bonds are created between the author and reader (34).

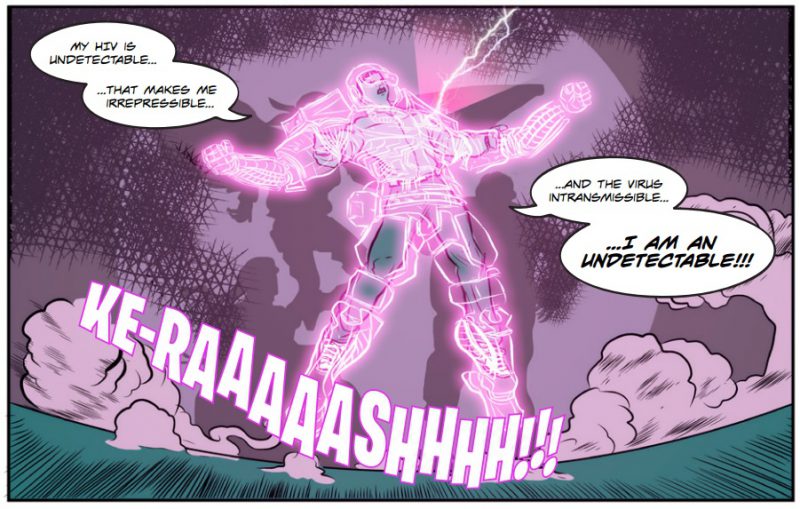

The second type of health-focused comics are those used for educational purposes (4). One example of this is the Undetectables comic book series, which appeared as part of the Undetectables Intervention (UI), designed to increase viral suppression among socially vulnerable people living with HIV in New York City (5). The intervention contained two other elements: assignment to interdisciplinary adherence support teams and a financial incentive. Authors describe the intervention as “…a superhero-themed social marketing and patient education campaign that employed graphic novels to valorize medication adherence as a heroic act to protect individual and community health” (5). All three issues can be accessed freely online (35). The graphic below is one strip from the first issue of the comic (35):

Study authors conducted a longitudinal analysis to determine the effectiveness of the intervention over time, and used qualitative exit interviews to explore barriers, facilitators, and mechanisms that contributed to the observed effect (5). Quantitative analysis (n=502 participants) revealed that virally supressed time-points increased from 67% pre-enrollment to 82% post-enrollment; the proportion of the sample virally suppressed at all time points increased from 39% pre-enrollment to 62% post-enrollment. Qualitative analysis (n=30 participants) indicated that the intervention increased adherence in two ways: by attaching worth to viral suppression, and by increasing motivation to achieve and maintain suppression (5).

Fotonovela

The fotonovela — literally a “photonovel” — is a type of comic book that uses photographic images instead of hand-drawn illustrations alongside narrative text and/or speech bubbles (14). Widely read in Latin America, fotonovelas emerged from the romantic fiction genre (14) and utilize dramatic storytelling and photography to fill knowledge gaps and encourage behaviour change (36). Fotonovelas integrate cultural norms and realistic, attractive characters into storylines, delivering sensitive informative in a meaningful way (6, 37).

Literature addressing the effectiveness of fotonovelas concerning HIV/AIDS appears to be sparse. Guys like you (Spanish: Chicos como tú) is one fotonovela that outlines issues within the Latin-American community in Toronto; it was developed with the intent of raising awareness in both gay and Latino communities (38). A second fotonovela, It looks like rain…put on your hat, my friend (Spanish: Parece que va a llover…compadre, ponte el sombrero) was designed in California for Latino immigrant day labourer men who have sex with men and women (39). Authors found that the fotonovela was effective, as it initiated discussion of high-risk behaviours and increased knowledge of HIV and other STIs (39).

The Rural Women’s Health Project (RWHP) is an organization in Florida that develops fotonovelas to reach people with low literacy skills or cross-cultural communication barriers (40). RWHP and the non-profit Farmworker Justice have partnered together and developed a series of HIV/AIDS-related fotonovelas and comics for migrant and seasonal farmworkers in the U.S. that can be found online (41). The following example is taken from a fotonovela designed for female farmworkers, and is available in English and Spanish (42):

While no peer-reviewed literature examining the effectiveness of fotonovelas and HIV appeared in our search results, there are several studies detailing interventions with fotonovelas for other health conditions that appear to have a positive impact: human papillomavirus vaccine (6), depression (7), and second hand smoking (8).

Evidence for comics as a health education tool

Available evidence for the effectiveness of comics as a health education tool is limited; studies primarily evaluate what information was learned from reading the comic (which is no different from how a plain-text document might be evaluated) (2). Aside from the aforementioned studies, there appear to be few HIV/AIDS comic interventions featured in peer-reviewed literature that demonstrate effectiveness, though there are some studies from the late 1980s and 1990s (43). However, more recent peer-reviewed literature has examined the effect of using comics to communicate health information regarding other health conditions:

- Two vaccine information flyers, one developed by the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) and the other a comic strip (adapted from the CDC flyer) were compared to determine the effects of each flyer (44). Adults at an ambulatory care centre in Queens, New York were randomly assigned to view the CDC flyer (n=132) or the adapted comic (n=133). Attitudes towards the flyer, perceived educational content, intention to seek more information, and motivation to become immunized were measured using a survey. Compared to the CDC flyer, authors found that the comic strip was positively evaluated, having a statistically significant effect on participant’s attitudes and perception of being informative (44).

- In a similar study, participants recruited in a supermarket (n=204) in Auckland, New Zealand, were randomized to read one of four leaflets about gout: three leaflets contained an image, and one contained solely text (45). Of the three leaflets that presented an image, one was a single-frame cartoon. The leaflets with illustrations were perceived as more visually appealing, but the comic was the only image that was better than text at conveying treatment information. Authors concluded that pictures helped to increase the visual appeal of the materials and were helpful in understanding health information (45).

- Another study evaluated the effectiveness of a culturally tailored fotonovela designed to educate Latino dementia caregivers in the U.S. (46). Oftentimes, caregivers have low literacy levels, less accurate knowledge of dementia, and suffer from stress and depression. Latino caregivers were randomly assigned to either the Fotonovela Condition (n=55) or the Usual Information Condition (n=55). Participants in the Fotonovela Condition received a 16-page booklet featuring a dramatic storyline illustrating key skills, like managing difficult behaviours and using adaptive coping strategies. The Usual Information Condition utilized a text pamphlet that provided standard information and educational materials about dementia and caregiving. Results demonstrated that participants in the fotonovela condition demonstrated significantly greater reductions in levels of depressive symptoms. Additionally, the fotonovela was referred to more by participants in this condition compared to those who received the pamphlet (46).

In addition to the above studies, medical comics in general have been including in training, improving health care, bioethics, and patient experiences of treatments for illness (47). Numerous peer-reviewed articles contend that graphic medicine can support patients, families, and health care providers by:

- fostering an environment (i.e. the “world” of a comic) that is less intimidating than traditional health information settings (47);

- viewing one’s situation from a different perspective — a doctor can better appreciate a patient’s experience, and vice-versa (2);

- improving health literacy through the carefully designed interplay of words and pictures (4);

- using a narrative that makes complex topics easier to understand (3);

- creating an effective depiction of time via spatial relationships between images, which can demonstrate cause-and-effect scenarios (e.g. the effect of taking medication) (4);

- juxtaposing different illustrations on the same page to contrast healthy or unhealthy disease states, or to compare external symptoms with internal processes (4);

- offering companionship, which can help to reduce feelings of isolation (2, 17);

- providing reassurance, increasing self-awareness, and creating a starting point for discussion with health care workers or family (3).

Creating a comic or fotonovela as a health education tool

An article published in 2019 in the Journal of Visual Communication and Medicine discusses the design, colour use, character choice, length, and use of humour in medical comics (48). Notably, the entire article (except for the abstract) is a comic. Selected points from this article encourage the illustrator and writer to:

- maximize readability by using large text and everyday language;

- create characters that reflect the audience and their culture;

- use abstract face drawings so that more people can see themselves in the narrative;

- signal important points to the reader so they can prioritize important information;

- minimize the colour palette by using two or three contrasting colours (48).

Additionally, the Rural Women’s Health Project discusses what needs to be included in a fotonovela so that it is effective in the Hispanic community. Fotonovelas should be written at an appropriate literacy level and include:

- images that represent the community;

- popular language;

- accepted role models;

- practical solutions to problems (40).

Generally, there appears to be a limited amount of literature that describes how to design or evaluate a comic or fotonovela for health promotion purposes. Additionally, some doctors and patients may be biased against comics, thinking that they are juvenile, simplistic, and frivolous; thus, it is important that appropriate comics are identified and distributed to those who would gain the most benefit from them (1). Furthermore, offering comics to patients may require an educator to review and assess their accuracy (4).

Factors that may impact local applicability

This review discusses comics, a combination of visual art (either drawn or photographed) and text that is found in comic books, graphic novels, fotonovelas, and on posters. While comics do have a broad appeal, some individuals may not be able to read comics (e.g. those with eyesight problems or low literacy) while others may not regularly read this type of communication (48). Additionally, this review focused on comics aimed at residents of high-income settings and did not consider comics intended for audience in low-income settings.

What we did

We searched Medline (including Epub Ahead of Print, In-Process & Other Non-Indexed Citations) using text terms (photo-novel* or photo novella* or Fotonovela* or comics or graphic novel*). Searches were conducted on January 6, 2020 and results limited articles published since 2009. Reference lists of identified articles were also searched. Google searches using various combinations of the above listed terms were also conducted. The search yielded 350 references from which 47 were included.

Reference list

- Green MJ, Myers KR. Graphic medicine: Use of comics in medical education and patient care. British Medical Journal. 2010;340:c863.

- McNicol S. Humanising illness: Presenting health information in educational comics. Medical Humanities. 2014;40(1):49–55.

- McNicol S. The potential of educational comics as a health information medium. Health Information & Libraries Journal. 2017;34(1):20–31.

- Ashwal G, Thomas A. Are comic books appropriate health education formats to offer adult patients? AMA Journal of Ethics. 2018;20(1):134–40.

- Ghose T, Shubert V, Poitevien V, Choudhuri S, Gross R. Effectiveness of a viral load suppression intervention for highly vulnerable people living with HIV. AIDS & Behavior. 2019;23(9):2443–52.

- Chan A, Brown B, Sepulveda E, Teran-Clayton L. Evaluation of fotonovela to increase human papillomavirus vaccine knowledge, attitudes, and intentions in a low-income Hispanic community. BMC Research Notes. 2015;8:615.

- Sanchez K, Killian MO, Eghaneyan BH, Cabassa LJ, Trivedi MH. Culturally adapted depression education and engagement in treatment among Hispanics in primary care: Outcomes from a pilot feasibility study. BMC Family Practice. 2019;20(1):140.

- Unger JB, Soto DW, Rendon AD, Baezconde-Garbanati L, Cruz TB. Empowering Hispanic multiunit housing residents to advocate for smokefree policies: A randomized controlled trial of a culturally tailored fotonovela intervention. Health Equity. 2019;3(1):198–204.

- Kelley B. Sequential art, graphic novels, and comics. Sequential Art Narrative in Education. 2010;1(1):10.

- Eisner W. Graphic storytelling and visual narrative. Paramus, N.J.: Poorhouse Press; 1996.

- McCloud S, Manning A. Understanding comics: The invisible art. IEEE Transactions on Professional Communications. 1993;41(1):66–9.

- Spiegelman A. Maus. New York: Pantheon Books; 1986.

- Watterson B. About Calvin and Hobbes. 2020. Available from: https://www.calvinandhobbes.com/about-calvin-and-hobbes/. Accessed January 15, 2020.

- Taylor C. Fotonovela. In: Shaw L, Dennison S. Pop culture Latin America!: Media, arts, and lifestyle. Santa Barbara, California: ABC-CLIO Inc. 2005.

- Carleton S. Drawn to change: Comics and critical consciousness. Labour/Le Travail. 2014;73:151–77.

- Green MJ, Mahato M. Graphic medicine: The best of 2018. Journal of the American Medical Association. 2018;320(24):2510–1.

- Williams IC. Graphic medicine: Comics as medical narrative. Medical Humanities. 2012;38(1):21–7.

- King AJ. Using comics to communicate about health: An introduction to the symposium on visual narratives and graphic medicine. Health Communication. 2017;32(5):523–4.

- Gessell P. Guru of graphic medicine. Canadian Medical Association Journal. 2016;188(17–18):E541.

- Gettelman E, Murrmann M. The enemy in your pants: The military’s decades-long war against STDs. 2010. Available from https://www.motherjones.com/media/2010/05/us-military-std-posters/. Accessed January 15, 2020.

- Hansen J. Social Welfare History Project: American Social Health Association. 2012. Available from: https://socialwelfare.library.vcu.edu/programs/health-nutrition/american-social-health-association/. Accessed January 15, 2020.

- Mungia R. Protect yourself: Venereal disease posters of World War II. Los Angeles: Boyo Press; 2014.

- Oatman-Stanford H. How the military waged a graphic-design war on venereal disease. 2015. Available from https://www.collectorsweekly.com/articles/a-graphic-design-war-on-venereal-disease/. Accessed January 16, 2020.

- Gaiser ML. The other ‘VD’: The educational campaign to reduce venereal disease rate during World War II. 2016. Available from: https://cupola.gettysburg.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1551&context=student_scholarship. Accessed January 16, 2020.

- Posen A. Them days is gone forever. 1943. Available from: https://collections.nlm.nih.gov/catalog/nlm:nlmuid-101438719-img. Accessed January 15, 2020.

- McAllister MP. Comic books and AIDS. The Journal of Popular Culture. 1992;26(2):1–24.

- Villemez J. The first gay character in a comic strip. 2019. Available from http://www.epgn.com/columns/our-history-our-future/15607-the-first-gay-character-in-a-comic-strip. Accessed January 16, 2020.

- Trudeau G. Doonesbury – April 6, 1989. 1989. Available from: https://www.gocomics.com/doonesbury/1989/04/06. Accessed January 16, 2020.

- Czerwiec MK. Taking turns: Stories from HIV/AIDS care unit 371. University Park, Pennsylvania: Pennsylvania State Univeristy Press; 2017.

- Czerwiec MK. Home/Books/Taking turns. 2017. Available from: https://comicnurse.com/book/taking-turns/. Accessed January 20, 2020.

- O’Connor M. Taking Turns: Stories from HIV/AIDS Care Unit 371. By MK Czerwiec (review). Oral History Review. 2019;46(1):236–9.

- Czerwiec MK, Huang MN. Hospice comics: Representations of patient and family experience of illness and death in graphic novels. Journal of Medical Humanities. 2017;38(2):95–113.

- Williams I. Autography as auto-therapy: Psychic pain and the graphic memoir. Journal of Medical Humanities. 2011;32(4):353–66.

- Cardamone T, Tuttle B, Alvarez R, Astasio J. Undetectables 1. 2014. Available from: https://liveundetectable.org/assets/files/The-Undetectables-Issue-1.pdf. Accessed January 20, 2020.

- USC School of Pharmacy. Increasing health literacy with fotonovelas. 2019. Available from: https://pharmacyschool.usc.edu/fotonovelas/. Accessed January 24, 2020.

- Unger JB, Cabassa LJ, Molina GB, Contreras S, Baron M. Evaluation of a fotonovela to increase depression knowledge and reduce stigma among Hispanic adults. Journal of Immigrant & Minority Health. 2013;15(2):398–406.

- Betancourt G. Guys like you: The fotonovela and the website. In: Lévy JJ, Dumas J, Ryan B, Thoër C. Minorités sexuelles, Internet et santé. Montréal, Québec: Presses de l’Université du Québec. 2011.

- Estremera D, Arevalo M, Armbruster J. Parece que va a lover…compadre, ponte el sombrero [It looks like rain…Put on your hat, my friend]: An HIV/STD risk awareness fotonovela for Latino immigrant day laborers. 2002. Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/stdconference/2002/abstracts/2002confabposter6.htm. Accessed January 24, 2019.

- Rural Women’s Health Project. The fotonovela. 2020. Available from: https://www.rwhp.org/fotonovela.html. Accessed January 24, 2020.

- Farmworker Justice. Fotonovela (tag). 2020. Available from: https://www.farmworkerjustice.org/resources/tag/health/fotonovela. Accessed January 24, 2020.

- Farmworker Justice, Rural Women’s Health Project. A light at the store/Una luz en la tienda. 2009. Available from: https://www.farmworkerjustice.org/sites/default/files/documents/9.2%20Light.pdf. Accessed January 24, 2020.

- Gillies P, Stork A, Bretman M. Streetwize UK: A controlled trial of an AIDS education comic. Health Education Research. 1990;5(1):27–33.

- Muzumdar JM, Pantaleo NL. Comics as a medium for providing information on adult immunizations. Journal of Health Communication. 2017;22(10):783–91.

- Krasnoryadtseva A, Dalbeth N, Petrie KJ. The effect of different styles of medical illustration on information comprehension, the perception of educational material and illness beliefs. Patient education and counseling. 2019. [Epub ahead of print].

- Gallagher-Thompson D, Tzuang M, Hinton L, Alvarez P, Rengifo J, Valverde I, et al. Effectiveness of a fotonovela for reducing depression and stress in Latino dementia family caregivers. Alzheimer Disease & Associated Disorders. 2015;29(2):146–53.

- Towey F. Conference: Comics and medicine. Lancet Oncology. 2014;15(9):927–8.

- Waite M. Writing medical comics. Journal of Visual Communication in Medicine. 2019;42(3):144–50.

Suggested citation

Rapid Response Service. The use of comic books, graphic novels, and fotonovelas as a health promotion tool. Toronto, ON: Ontario HIV Treatment Network; February, 2020.

Prepared by

Danielle Giliauskas and David Gogolishvili

Photo credit